The grim reality of modern slavery, known as human trafficking (HT), affects millions globally. The U.S. Department of State estimates that between 4 and 27 million individuals are trapped in various forms of exploitation worldwide. Within the United States, a startling number of trafficking victims, ranging from 28% to 50%, encounter health care professionals during their captivity. Despite this contact, these victims often go unrecognized and unassisted. This highlights a critical gap in health care: the need for effective education and training programs on human trafficking for health care providers.

This article delves into the crucial question: What Programs Educate Health Care Providers On Human Trafficking? By examining the landscape of current educational initiatives and drawing insights from a key study on emergency department (ED) interventions, we aim to shed light on the types of programs that can effectively enhance health care professionals’ ability to identify, support, and refer victims of human trafficking. Understanding these programs is paramount to transforming health care settings into vital points of intervention in the fight against modern slavery.

The Undeniable Role of Healthcare Providers in Combating Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is not solely a legal, law enforcement, or social service issue; it is fundamentally a health care crisis. Victims of trafficking endure a wide spectrum of physical and psychological health problems stemming directly from their exploitation. These issues range from injuries from physical and sexual abuse, malnutrition, infectious diseases due to unsanitary living conditions, to severe mental health conditions like PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Healthcare providers, spanning physicians, nurses, social workers, and other allied health professionals, are often the first and sometimes only point of contact these victims have with the outside world while still under the control of their traffickers.

Studies underscore this point, revealing that a significant proportion of trafficking victims interact with health care systems while being trafficked. Emergency Departments, in particular, are critical locations for potential intervention. ED staff are trained to recognize and respond to sensitive issues like child abuse and domestic violence, positioning them ideally to identify trafficking victims. However, despite this potential, a considerable gap exists. Many health care professionals lack adequate training on the specific signs and indicators of human trafficking, the unique health needs of trafficking survivors, and the appropriate protocols for intervention and referral. Research indicates that while many ED personnel recognize human trafficking as a problem, a far smaller percentage feel confident in their ability to identify victims, and even fewer have received formal training on the issue.

This lack of training represents a significant missed opportunity. Equipping health care providers with the necessary knowledge and skills to recognize and respond to human trafficking is not just an ethical imperative; it is a practical necessity in the fight against this pervasive crime. By understanding the available educational programs and advocating for their wider implementation, we can empower health care professionals to become effective first responders in identifying and assisting trafficking victims.

A Study on Educational Intervention in Emergency Departments: A Model for Program Development

To understand the impact of education, it’s valuable to examine studies that have directly assessed the effectiveness of training programs for health care professionals. One such study, conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area, provides compelling evidence for the positive impact of even brief educational interventions. This research, which focused on emergency department providers, offers valuable insights into the structure and content of effective human trafficking education programs.

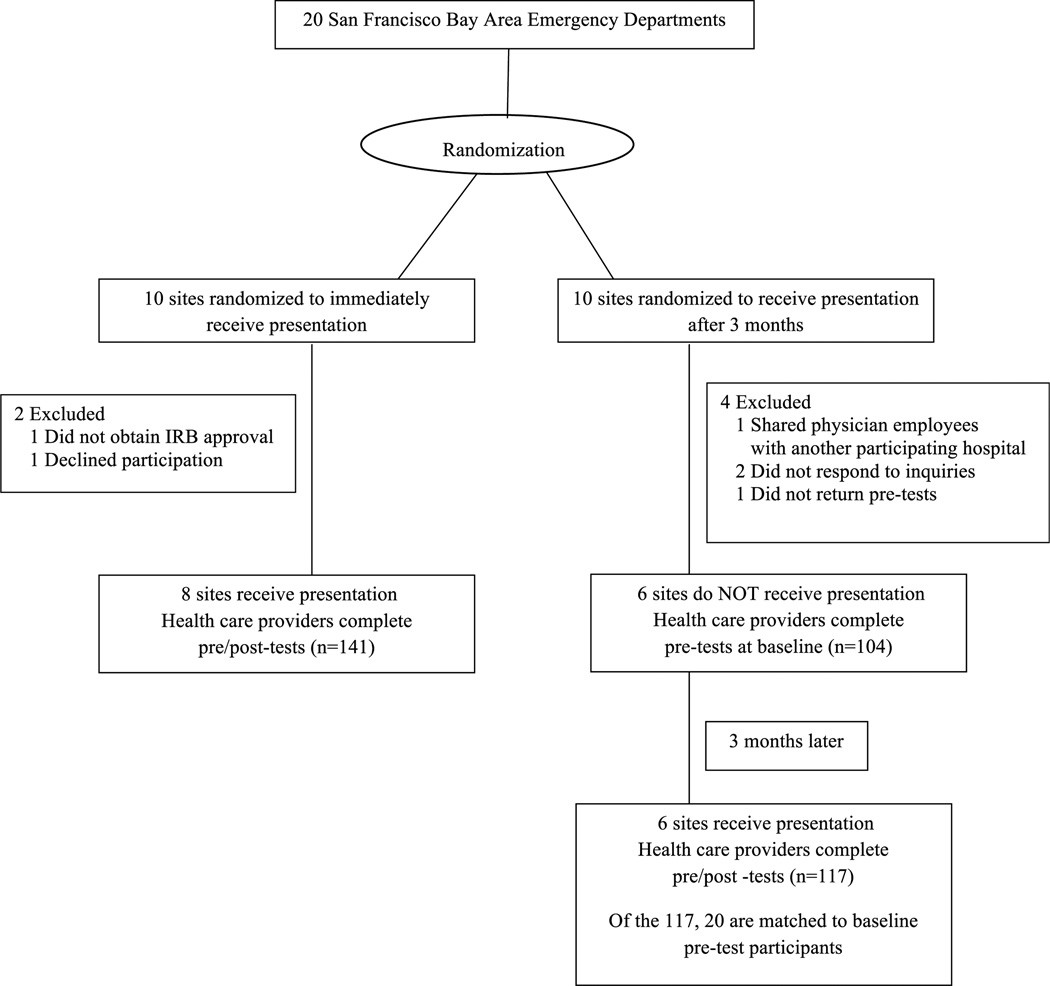

The study employed a randomized controlled trial design across 20 of the largest Emergency Departments in the San Francisco Bay Area. These EDs were divided into two groups: an intervention group that received an immediate educational presentation and a delayed intervention comparison group. This delayed intervention group design is a robust method to assess the true impact of the educational program by comparing changes in knowledge and awareness in the intervention group against a control group over time.

The educational intervention itself was a standardized presentation, developed in collaboration with the San Jose Police Department, a recognized leader in law enforcement and community education on human trafficking. The presentation was designed to be concise and impactful, delivered within existing departmental meetings or Grand Rounds to minimize disruption to busy ED schedules. Crucially, both short (25-minute) and long (60-minute) versions were developed, ensuring accessibility across different time constraints while maintaining core content.

The content of the educational program was carefully structured to provide essential information and practical tools. It covered key areas including:

- Background on Human Trafficking: Providing a foundational understanding of the scope and nature of human trafficking, including local examples to highlight its relevance to the Bay Area.

- Relevance of HT to Health Care: Emphasizing why human trafficking is a critical health issue and the unique role health care providers play in identification and intervention.

- Clinical Signs to Identify Potential Victims: Equipping providers with concrete, observable indicators and red flags that might suggest a patient is a victim of trafficking. This is vital for translating awareness into actionable identification.

- Referral Options for Potential Victims: Providing practical resources and pathways for assisting victims, including contact information for 911, the National Human Trafficking Hotline, and hospital social workers. Knowing who to call and how to connect victims with help is a crucial component of effective intervention.

The study measured the impact of this educational intervention through pre- and post-tests assessing changes in participants’ attitudes, knowledge, and self-reported recognition of human trafficking victims. The primary outcomes focused on:

- Perceived Importance of HT Knowledge: Assessing whether the education increased providers’ understanding of the relevance of human trafficking to their professional roles.

- Self-Rated Knowledge of HT: Measuring changes in providers’ confidence in their own knowledge about human trafficking.

- Knowledge of Referral Resources: Evaluating whether the program effectively increased awareness of who to contact when encountering a potential trafficking victim.

- Suspicion of Past Patient as HT Victim: Gauging if the education increased providers’ likelihood of considering whether a patient they had seen might have been a trafficking victim, indicating a heightened sense of awareness and vigilance.

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

The results of this study were statistically significant and highly encouraging. The educational intervention led to a substantial increase in ED providers’ self-rated knowledge of human trafficking and, critically, their knowledge of who to call for assistance. Furthermore, the intervention significantly increased the proportion of providers who reported suspecting that a patient might be a victim of human trafficking. This indicates that the education not only imparted knowledge but also heightened awareness and sensitivity to the issue, translating into a greater likelihood of victim identification. Interestingly, the study found that the length of the presentation (25 vs. 60 minutes) did not significantly impact the effectiveness, suggesting that even brief, well-designed educational modules can be impactful.

This study provides a strong model for developing effective programs to educate health care providers on human trafficking. Its key features – concise, targeted content delivered in accessible formats, collaboration with law enforcement experts, and a focus on practical knowledge and referral pathways – offer a blueprint for successful program implementation.

Expanding the Scope: Types of Programs Educating Healthcare Providers

While the ED-focused study provides valuable insights, it is crucial to consider the broader landscape of programs designed to educate health care providers on human trafficking. Effective educational initiatives need to be diverse, adaptable, and reach a wide range of health professionals across various settings. Here are some key types of programs and approaches currently being implemented and advocated for:

1. Continuing Medical Education (CME) and Continuing Nursing Education (CNE) Modules:

- Format: These are often online, self-paced modules that can be completed by health professionals to earn CME/CNE credits, a requirement for maintaining licensure in many fields.

- Content: CME/CNE modules can delve into the epidemiology of human trafficking, the health consequences for victims, identification protocols, legal and ethical considerations, and trauma-informed care approaches.

- Advantages: Accessibility, flexibility for busy professionals, standardized content, and incentivized participation through credit systems.

- Examples: Numerous organizations, including professional medical societies, universities, and anti-trafficking NGOs, offer online CME/CNE courses on human trafficking.

2. In-Person Workshops and Training Sessions:

- Format: Interactive sessions delivered in hospitals, clinics, medical schools, and conferences.

- Content: Workshops can incorporate case studies, simulations, role-playing, and expert presentations from medical professionals, law enforcement, and survivor advocates. These sessions allow for deeper engagement, Q&A, and networking.

- Advantages: Facilitates active learning, allows for tailored content to specific settings or professional groups, builds community and collaboration among participants.

- Examples: Hospitals and health systems are increasingly incorporating in-person human trafficking training into staff onboarding and ongoing professional development. Organizations like HEAL Trafficking and the National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center (NHTTAC) provide in-person training programs and resources.

3. Integration into Medical and Nursing School Curricula:

- Format: Longitudinal integration of human trafficking education into undergraduate and graduate medical and nursing education.

- Content: This approach ensures that future generations of health professionals receive foundational knowledge on human trafficking as part of their core training. Content can be incorporated into courses on public health, ethics, social determinants of health, behavioral health, and clinical rotations.

- Advantages: Systematic and comprehensive approach, reaches future professionals early in their careers, normalizes human trafficking as a core health issue.

- Examples: Medical schools and nursing programs are beginning to incorporate human trafficking curricula, often driven by student advocacy and recognition of the importance of this issue. Organizations like the American Medical Association and the American Nurses Association have advocated for the inclusion of human trafficking education in medical and nursing education.

4. Specialized Training for Specific Healthcare Settings:

- Format: Tailored programs designed for professionals working in specific areas like emergency departments, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, mental health, and school nursing.

- Content: These programs address the unique challenges and opportunities for identification and intervention within specific practice settings. For instance, pediatric training might focus on child trafficking indicators, while OB/GYN training might address trafficking in pregnant women.

- Advantages: Highly relevant and practical, addresses the specific needs and contexts of different healthcare specialties, maximizes the impact of training within targeted areas.

- Examples: Hospitals with high patient volume in specific departments may develop specialized training modules for their staff. Professional organizations in specific medical fields may also offer tailored resources and training.

5. Public Awareness Campaigns and Community Education:

- Format: Broader initiatives aimed at raising awareness among the general public and community stakeholders, including patients, community health workers, and social service providers.

- Content: These campaigns can utilize public service announcements, brochures, websites, and community events to disseminate information about human trafficking, its signs, and available resources.

- Advantages: Creates a more informed and supportive community environment, reduces stigma, encourages reporting, and strengthens the overall network of support for trafficking victims.

- Examples: Government agencies, NGOs, and healthcare organizations often conduct public awareness campaigns during Human Trafficking Awareness Month (January) and throughout the year.

Moving Forward: Enhancing and Expanding Educational Programs

While progress has been made in developing and implementing educational programs on human trafficking for health care providers, significant work remains. To maximize the impact of these programs and ensure that all health professionals are adequately prepared to respond to human trafficking, several key areas need to be addressed:

- Mandatory Education Policies: Advocating for policies that mandate human trafficking education for health care professionals as a condition of licensure or hospital accreditation. This would ensure that all professionals receive at least baseline training.

- Standardized Curricula and Competencies: Developing national standards for human trafficking education in health care, outlining core competencies and essential content areas. This would ensure consistency and quality across different programs.

- Increased Funding and Resources: Securing dedicated funding streams to support the development, implementation, and evaluation of human trafficking education programs. This includes funding for curriculum development, training materials, faculty training, and program evaluation.

- Evaluation and Research: Conducting rigorous evaluations of existing educational programs to assess their effectiveness, identify best practices, and refine program design. Further research is needed to understand the long-term impact of education on provider behavior and patient outcomes.

- Collaboration and Partnerships: Strengthening collaboration between health care organizations, law enforcement, anti-trafficking NGOs, survivor advocates, and academic institutions to develop and deliver comprehensive and impactful educational programs.

- Trauma-Informed and Survivor-Informed Approaches: Ensuring that all educational programs are grounded in trauma-informed principles and incorporate the perspectives and expertise of trafficking survivors. Survivor voices are invaluable in shaping effective and compassionate training.

Conclusion: Empowering Healthcare to Combat Human Trafficking through Education

Educating health care providers on human trafficking is not merely an option; it is an ethical imperative and a critical component of a comprehensive strategy to combat modern slavery. The study on ED interventions, along with the broader landscape of educational programs, demonstrates the power of education to increase awareness, knowledge, and ultimately, the identification and support of trafficking victims.

By investing in and expanding these educational initiatives, we can transform health care settings into crucial frontlines in the fight against human trafficking. Empowered with the right knowledge and skills, health care professionals can become vital allies in identifying, assisting, and offering hope to those trapped in the shadows of exploitation, moving us closer to a world where modern slavery is no longer tolerated. The question is not if we should educate health care providers, but how we can best implement and scale effective programs to reach every professional and create a truly trafficking-free world.

References