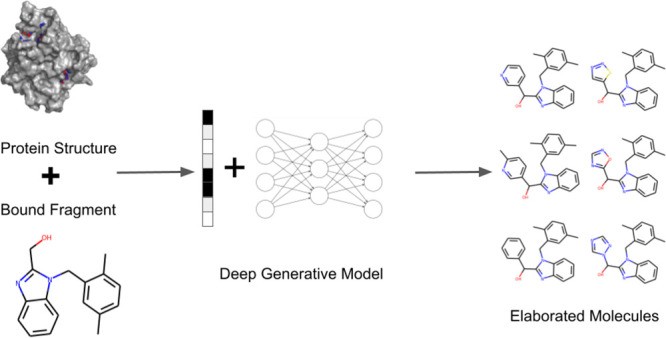

Deep generative models have garnered significant attention for their potential in scaffold elaboration within drug discovery. However, their practical application in fragment-to-lead campaigns has been limited due to challenges in incorporating local protein structure and user-defined design hypotheses. To address these limitations, we introduce STRIFE (Structure Informed Fragment Elaboration), a novel computational method designed for effective fragment elaboration. STRIFE leverages fragment hotspot maps (FHMs) derived from a protein target to provide interpretable structural insights to its generative model. This innovative approach enables the rapid generation of elaborations with pharmacophores that are complementary to the protein’s binding site. Extensive evaluation demonstrates that STRIFE surpasses existing structure-unaware fragment elaboration methods in proposing highly ligand-efficient elaborations. Furthermore, STRIFE offers users the flexibility to incorporate their own design hypotheses alongside the pharmacophoric information automatically extracted from the protein target’s FHM. This advancement holds significant promise for accelerating and enhancing fragment-based drug discovery efforts, especially for researchers involved in De-foa-0001625 Early Career Research Program related fields, seeking innovative tools for molecular design and optimization.

Introduction

Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) is increasingly recognized as a powerful strategy for the rational design of novel therapeutic compounds.1,2 FBDD campaigns initiate drug development by identifying small, fragment-like molecules that exhibit weak binding affinity to a target protein. These fragments serve as starting points for the subsequent development of high-affinity binders. Compared to traditional drug design approaches, FBDD offers several key advantages. Firstly, the use of low molecular weight fragments allows for greater control over the physicochemical properties of the resulting drug molecule compared to starting with larger, drug-like molecules.3 Secondly, FBDD facilitates a more efficient exploration of chemical space. A study in 20054 reported that fragment libraries exhibited hit rates 10 to 1000 times higher than standard high-throughput screening assays. Consequently, fragment-based approaches offer an improved probability of identifying a starting point for drug development and enhanced control over the subsequent optimization process.

Following the identification of fragment hits against a specific target, three primary strategies are employed to evolve a lead molecule with high binding affinity:5

- Elaboration (Growing): This strategy involves selecting a single fragment and adding functional groups to extend its interactions and affinity with the target protein.

- Fragment Linking: This approach targets two fragments that bind concurrently in proximity within the protein’s binding site. A molecular bridge is designed to connect these fragments, resulting in a single molecule incorporating both fragments as substructures.

- Fragment Merging: This strategy is applied when two or more fragments bind to overlapping regions of the protein. The aim is to design molecules that integrate key structural motifs from each fragment into a single entity.

Currently, the design of elaborations, linkers, and merged molecules is largely driven by the expertise of medicinal chemists and computational chemists. These experts leverage standard computational tools and their profound understanding of chemical principles to propose promising molecular designs. However, this expert-driven approach can be limited by implicit biases based on past project successes and failures. Furthermore, when dealing with a large number of hits from extensive fragment screens, it becomes impractical for human experts to objectively evaluate all possible elaboration or linking opportunities for their suitability.

Recent years have witnessed a surge of interest in developing machine learning models to accelerate and enhance the generation and screening of potential drug candidates. Researchers have explored diverse molecular representations, including SMILES strings,6 molecular graphs,7 SELFIES (self-referencing embedded strings),8 and atomic density grids,9 coupled with various deep learning architectures, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs),10 variational autoencoders (VAEs),11 and recurrent neural networks (RNNs).12 To generate molecules with optimized properties, several multiobjective optimization techniques have been proposed, including gradient descent,13 reinforcement learning,12 Bayesian optimization,11 and particle swarm optimization.14

Early generative models typically created molecules “from scratch.” However, recent efforts have focused on developing deep learning-based methods specifically to improve the efficiency of fragment-to-lead campaigns. Graph-based approaches for scaffold elaboration have been pioneered by Lim et al.15 and Li et al.,16 which utilize a fragment as input and generate sets of molecules that contain the original fragment as a substructure. Arús-Pous et al.17 introduced Scaffold-Decorator, a SMILES-based model18 that provides users with control over elaboration by allowing them to specify exit vectors on the fragment, guiding the direction of molecular growth. However, these existing approaches lack the ability to specify desired elaboration size and, crucially, do not directly account for protein structure during the generation process. This limitation hinders their ability to ensure that generated elaborations are of an appropriate size to fit within the target protein’s binding pocket.

More recently, we developed DEVELOP,19 a fragment-based generative model for linking and growing molecules, building upon our earlier DeLinker model.20 DEVELOP allows for the incorporation of pharmacophoric constraints and control over linker/elaboration length, providing greater precision in the design of generated molecules. Concurrently with DEVELOP’s development, Fialková et al.21 introduced LibINVENT, an extension of Scaffold-Decorator,17 capable of designing core-sharing chemical libraries using specific chemical reactions. LibINVENT also enables users to generate molecules with high 3D similarity to known active molecules through reinforcement learning. However, both DEVELOP and LibINVENT rely on pre-existing active molecules or human-defined pharmacophoric constraints to guide molecule generation, making them more suited for R-group optimization than for de novo compound design against novel targets.

In a complementary direction, database-driven approaches have emerged as valuable tools for compound design. CReM,22 a recent method, operates on the principle that a fragment within a larger molecule can be exchanged with another fragment observed in a similar local context in different molecules. CReM identifies potential elaborations by searching a molecular database for fragments that share the local context of a specified exit vector. Other database-based methods incorporate protein-specific information. FragRep23 takes a protein and a bound ligand as input and proposes modifications to the ligand by fragmenting it and replacing fragments with similar fragments from a database that would maintain protein-ligand interactions. DeepFrag24 utilizes a structure-aware convolutional neural network to select optimal elaborations from a database of potential extensions.

For de novo molecule generation, several generative models have been developed to extract information directly from the target protein. Skalic et al.25 used a GAN26 to generate ligand shapes that are complementary to the binding pocket, subsequently employing a shape-captioning network to generate molecules matching these shapes. Masuda et al.27 encoded atomic density grids for both ligands and proteins into separate latent representations and trained a model to generate 3D ligand densities conditioned on protein structure, which were then translated into discrete molecular structures. While these models demonstrated the generation of ligands dependent on learned structural representations, they do not readily accommodate the incorporation of design hypotheses from human experts. Kim et al.28 utilized water pharmacophore models to learn the locations of key protein pharmacophores, which were then used to construct training datasets of molecules with complementary pharmacophores. While this approach aligns well with standard drug discovery workflows, it necessitates training a separate deep learning model for each target, as each target requires a specific training set of compounds tailored to its water pharmacophores.

In this study, we present STRIFE (Structure Informed Fragment Elaboration), a novel generative model for fragment elaboration that extracts meaningful and interpretable structural information directly from the protein target to guide the elaboration process. Unlike existing fragment-based generative methods, STRIFE incorporates protein-specific information without relying on known ligands or human-specified pharmacophoric constraints. To facilitate seamless integration into fragment-to-lead campaigns, STRIFE is highly customizable. Beyond automatically extracting pharmacophoric information from the protein, STRIFE provides a user-friendly interface for incorporating user-defined design hypotheses, enabling the generation of elaborations aimed at satisfying specific pharmacophoric requirements. Through extensive evaluation using the CASF-2016 benchmark dataset,29 we demonstrate that STRIFE significantly outperforms existing fragment-based models,17,22 in generating ligand-efficient elaborations. We further showcase STRIFE’s practical applicability in real-world FBDD scenarios through two case studies derived from published literature. The first case study involves elaborating a fragment bound to N-myristoyltransferase, a crucial component in rhinovirus assembly and infectivity. STRIFE successfully generates elaborations remarkably similar to a potent known inhibitor.30 In the second case study, we demonstrate how user-specified design hypotheses can be incorporated into STRIFE, considering a fragment-inspired small molecule inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor reported by O’Connell et al.31 In this example, the elaboration proposed by O’Connell et al.31 induces a significant conformational change in a Tyrosine side chain. By manually specifying a design hypothesis to explore side-chain flexibility, we successfully recovered the original elaboration and generated a range of alternative elaborations predicted to induce similar side-chain movement.

Methods

We introduce STRIFE, our deep generative model for fragment elaboration. STRIFE requires three inputs from the user: a target protein structure, a bound fragment molecule, and the fragment’s exit vector, indicating the direction for elaboration. In our prior research,19 we demonstrated that imposing pharmacophoric constraints significantly enhances control over the types of functional groups added during fragment elaboration. STRIFE builds upon the approach presented in Imrie et al.,19 which used pharmacophoric constraints derived from known active molecules. STRIFE extends this concept by directly extracting pharmacophoric constraints from the protein structure itself, thereby broadening its applicability to a wider range of drug targets. Pharmacophoric information is extracted by calculating a fragment hotspot map32 (FHM), which identifies regions within the protein’s binding pocket that are likely to contribute positively to binding affinity. STRIFE then identifies pharmacophoric constraints that are likely to place a pharmacophore within a matching hotspot region and utilizes these constraints to guide the generation of elaborations.

Fragment Hotspot Maps

We employ the Hotspots API33 to calculate FHMs, implementing the algorithm described by Radoux et al.;32 in this study, all FHMs were generated using the default parameters defined by Curran et al.33 The FHM calculation process is as follows: Atomic propensity maps are initially calculated using SuperStar.34 SuperStar defines a grid encompassing the protein, with grid points spaced 0.5 Å apart. It utilizes data from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)35 to assign a propensity score for a given probe type at each grid point. A high propensity score indicates a particularly favorable interaction between two groups at a specific distance and angle, reflecting a higher frequency of occurrence in CSD structures. Once atomic propensity maps are calculated, FHMs are derived by weighting the scores at each grid point based on its degree of burial within the protein.

FHM scores are then calculated using small chemical probes, specifically an aromatic ring with different atoms at the substituent position. For apolar hotspot maps, the substituent is a methyl group; for acceptor and donor hotspot maps, the substituents are a carbonyl and an amine, respectively. These probes are positioned at all grid points with weighted propensity scores exceeding 15 and randomly rotated 3000 times about the center of the substituted atom. For each pose, each atom receives a score from the weighted propensity map, and probe scores are calculated as the geometric mean of the atom scores. Critically, if an atom clashes with the protein, it receives a score of zero, ensuring that any probe pose that clashes with the protein receives a geometric mean score of 0.

FHMs possess several advantageous properties. First, only grid points with weighted propensity scores above a threshold are sampled, and these scores are weighted by protein burial. This reduces the likelihood of identifying overly exposed regions as hotspots. Second, because clashing probe poses receive a score of zero, any region identified as a fragment hotspot must be able to accommodate a molecule of reasonable size. This reduces the risk of pursuing pharmacophores identified by the FHM that are inaccessible to elaborations due to steric constraints.

FHM Processing

STRIFE utilizes FHMs to guide the generative model in placing functional groups that can effectively interact with the target protein. As different hotspot map types serve distinct purposes, they undergo slightly different processing steps (Figure 1). Acceptor and donor hotspots are used to identify desirable pharmacophoric constraints, while apolar maps are used to confirm that the fragment is situated within a suitable binding site. For apolar maps, all grid points with values greater than 1 are retained, and all other points are discarded. Similarly, for acceptor and donor maps, grid points with values greater than 10 are retained. While Radoux et al.32 reported that values above 17 are generally predictive of fragment binding, we selected a threshold of 10 to achieve broader coverage; this parameter can be easily adjusted to focus on higher quality hotspots.

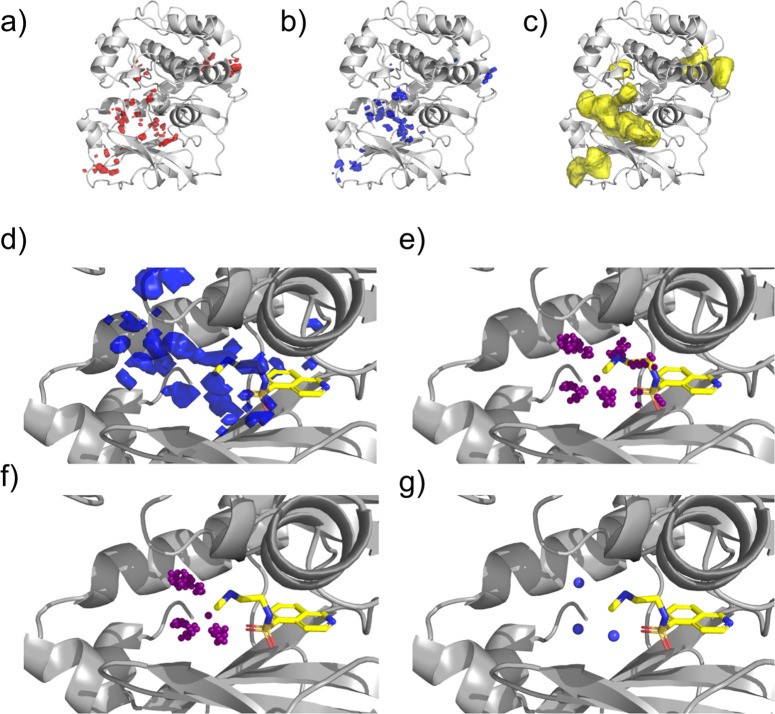

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Processing fragment hotspot maps: (a) acceptor hotspot map, (b) donor hotspot map, and (c) apolar hotspot map. A matching pharmacophore placed within a hotspot is likely to contribute significantly to binding affinity. (d) An unprocessed donor hotspot map in the vicinity of the fragment of interest. (e) Each sphere represents a voxel in the hotspot map. Voxels too distant from the fragment exit vector are discarded. (f) Voxels closer to another fragment atom than the exit vector are removed. (g) Voxels are clustered based on their spatial proximity. STRIFE aims to generate elaborations that position a matching ligand pharmacophore near a cluster centroid.

To process acceptor and donor maps, points located less than 1.5 Å or more than 5 Å from the fragment exit vector are discarded to limit elaborations to an appropriate length. These distance thresholds are chosen to reflect the iterative nature of fragment-to-lead campaigns, where small, incremental elaborations are typical. However, these thresholds are user-adjustable to accommodate longer or shorter elaborations.

A greedy clustering algorithm is employed to identify contiguous hotspot regions. The algorithm operates as follows: A cluster is initiated with a single point, and all unclustered points within 1 Å of this point are added to the cluster. For each point in the cluster, distances to all remaining unclustered points are calculated, and any points within 1 Å are added until no more unclustered points can be added. Once a cluster is complete, a new cluster is started by selecting a single unclustered point, and the process repeats until all points are assigned to a cluster. For each hotspot cluster, centroids are defined by calculating the mean position of points within the cluster. To reduce redundancy, if two cluster centroids are closer than 1.5 Å, the centroid associated with the smaller cluster is removed. Additionally, clusters smaller than eight points are removed, unless no clusters of eight or more points exist, in which case smaller clusters are retained.

Apolar maps are used in a final filtering step, based on the heuristic that molecules fully contained within an apolar hotspot region have a higher probability of binding to the protein. Therefore, if an acceptor or donor cluster centroid is not contained within an apolar hotspot region, it is filtered out. Furthermore, if all fragment atoms are not contained within an apolar hotspot, the fragment is deemed unsuitable for elaboration, and the algorithm terminates. While this may seem overly restrictive, apolar hotspot maps typically cover the majority of binding sites, and this filtering step can be easily bypassed if the user believes a fragment is a suitable candidate for elaboration despite not fully residing within an apolar hotspot.

The final output of this processing scheme is a set of 3D coordinates representing the remaining cluster centroids from the acceptor and donor maps (referred to as “pharmacophoric points”). In subsequent molecule generation steps, the goal is to generate elaborations that position matching functional groups in close proximity to these pharmacophoric points. While the described pipeline automates pharmacophoric point definition, STRIFE also provides a user-friendly functionality to manually define pharmacophoric points, enabling users to explore diverse design hypotheses (see Methods and Customizability sections).

Next, we describe how STRIFE utilizes these pharmacophoric points to generate elaborations with pharmacophores complementary to the target protein.

Generative Model

The generative model employed by STRIFE is similar to our previous model, DEVELOP,19 and is based on the constrained graph variational autoencoder framework proposed by Liu et al.7 STRIFE differs from DEVELOP in the structural information D provided to the model during molecule decoding (see Methods and STRIFE Algorithm sections). Given a fragment, f, and structural information, D, elaborations are generated as follows: Fragment f is represented as a graph. Each node v in the graph is assigned an h-dimensional vector representation z*v and a label lv, indicating the atom type of the node. A set of K* “expansion nodes,” zv1,···,z*vK, are generated by sampling from an h-dimensional standard normal distribution. Each expansion node is assigned a label by a linear classifier that takes and D* as input. These expansion nodes represent potential atoms that can be appended to the fragment.

Starting from the fragment exit vector, the model iteratively samples a node to add to the graph from the set of expansion nodes. To determine whether to form a bond between node v and node u, a neural network is used, taking the following input:

where t is the current time step. svt = [*zv, lv] is the concatenation of the latent vector and label at the tth time step. du,v is the graph distance between nodes u and v. Hj represents the average of all latent vectors at the j*th time step.

After adding a new node to the graph, a gated graph neural network36 updates the encodings for each node to reflect changes in its neighborhood. This iterative process continues until termination, at which point the final elaborated molecule is returned. Further details regarding the generative model framework can be found in our prior publications.19,20

STRIFE Algorithm

We have described how STRIFE utilizes fragment hotspot maps (FHMs)32 to obtain interpretable structural information and how, given a fragment, f, and structural information, D, elaborations can be generated. Here, we detail how these processes are integrated within the STRIFE algorithm. Specifically, we outline the conversion of 3D pharmacophoric points derived from FHMs into a structural information representation, D, used to guide elaboration generation.

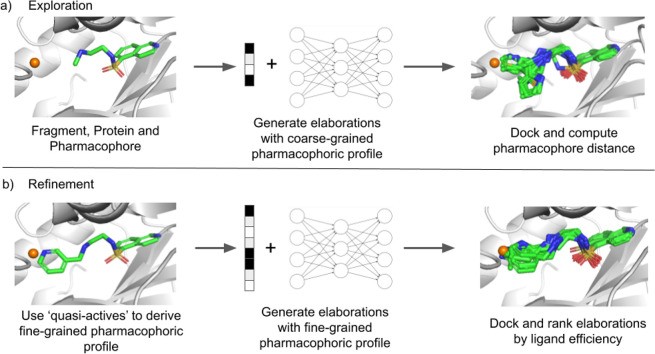

Structural information D can be provided to the generative model in two distinct formats. The first is a coarse-grained pharmacophoric representation, where the model receives a vector containing counts of hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrogen bond donors, and aromatic groups. The desired pharmacophoric profile of generated elaborations can be specified more precisely by including predicted path distances (shortest atom sequence connecting two points) from the exit vector to the pharmacophore. This fine-grained representation offers greater control over the types of elaborations generated. STRIFE employs both coarse-grained and fine-grained pharmacophoric information representations at different stages of the algorithm. In the exploration phase (Figure 2a), STRIFE uses the coarse-grained representation to generate a broad range of elaborations, which are then assessed for suitability. In the refinement phase (Figure 2b), fine-grained pharmacophoric profiles are derived from the most promising elaborations and used to generate further, more focused elaborations. Additional details are provided below and in the Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustration of STRIFE’s elaboration generation process, placing pharmacophores near specified pharmacophoric points. (a) Exploration phase: STRIFE generates elaborations using a coarse-grained pharmacophoric profile and docks them using constrained docking in GOLD.38 (b) Refinement phase: Elaborations that successfully placed a matching pharmacophore near the pharmacophoric point are used to derive a fine-grained pharmacophoric profile. STRIFE then generates elaborations using these fine-grained profiles. Resulting molecules are docked and ranked by predicted ligand efficiency.

In a typical fragment elaboration campaign, practitioners often work iteratively, making small elaborations to a fragment, optimizing it, and then making further elaborations to the optimized molecule. In this paper, we demonstrate STRIFE generating elaborations that place a pharmacophore close to a single pharmacophoric point at a time. For instance, if the set of pharmacophoric points includes one donor and one acceptor, STRIFE will generate a set of elaborations with a donor near the donor pharmacophoric point and another set with an acceptor near the acceptor pharmacophoric point. It does not attempt to satisfy both simultaneously unless explicitly instructed. STRIFE is capable of simultaneously targeting multiple pharmacophoric points, but this is recommended only if the pharmacophoric points are manually specified or carefully inspected, as certain pharmacophore combinations may be incompatible within a single elaboration. After obtaining pharmacophoric points from the FHM, STRIFE proceeds in two phases:

Exploration Phase

STRIFE aims to generate elaborations containing functional groups in close proximity to each pharmacophoric point. To achieve this, for each pharmacophoric point, we predict the atom-length distance between the fragment exit vector and the pharmacophoric point using a trained support vector machine.37 As the generative model requires a desired elaboration length, we use this atom-length prediction to control the length of proposed elaborations. To allow for the inclusion of rings and side chains in elaborations, we use several different desired elaboration lengths; if the predicted atom distance is p, we generate elaborations with requested lengths up to p + 4. In addition to elaboration size, the generative model needs a desired pharmacophoric profile. In the exploration phase, we use a coarse-grained pharmacophoric profile. As this profile does not specify a desired path distance between the exit vector and the ligand pharmacophore, the pharmacophores in generated elaborations will occupy a broad range of positions within the binding pocket.

The proposed elaborations are filtered (Supporting Information) and docked using the constrained docking functionality in GOLD,38 with the fragment structure provided as a constraint. Each molecule is docked 10 times, and the top-ranked pose is selected. For each top-ranked pose, we calculate the distance between the 3D pharmacophoric point and a matching pharmacophore in the molecule. We then identify molecules where this distance is less than 1.5 Å and select the top five molecules with the smallest distances between the pharmacophoric point and the ligand pharmacophore. If fewer than five molecules meet the 1.5 Å distance criterion, we select only those that do.

Refinement Phase

Molecules that successfully place a functional group near a pharmacophoric point provide valuable information. They are used to derive a more fine-grained representation of structural information, specifying the path distance between the exit vector and each ligand pharmacophore. We refer to these molecules as “quasi-actives” because they play a similar role to known active molecules in existing generative models. Having obtained a set of quasi-actives for each pharmacophoric point and used them to derive structural information vectors D1, D2,···, *D**n*, the user can either generate a fixed number of elaborations for each *D**i* or request a fixed total number of elaborations, where a structural information vector is randomly sampled from {*D**i}i = 1n for each elaboration. As before, generated molecules are filtered and docked using constrained docking in GOLD.38 Finally, each unique molecule, m*, is ranked by its ligand efficiency, calculated as the docking score divided by the number of heavy atoms. This ranking helps users prioritize a small set of elaborations for further consideration.

ADMET Filtering

To reduce the likelihood of proposing molecules with unfavorable ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) properties, we offer an optional post hoc filter based on the quantitative estimate of druglikeness (QED).39 The QED score considers various factors relevant to ADMET, such as hydrophobicity and molecular weight. It serves as a rapid indicator of molecules that might exhibit problematic ADMET characteristics.

Because the QED of an elaborated molecule is strongly influenced by the original fragment, we use the QED of the original fragment as a threshold for flagging molecules proposed by STRIFE. Specifically, a molecule is flagged if it is predicted to be “less druglike” than the original fragment. Users can also adjust the flagging threshold.

Customizability

Although STRIFE can automatically extract pharmacophoric points from a protein, real-world drug discovery often involves exploring user-defined design hypotheses. To facilitate this, STRIFE provides a user-friendly functionality for manually specifying pharmacophore locations in the protein context. The tool, illustrated in Figure 3, loads a lattice centered around the fragment exit vector into a molecule viewer. Users can manually select lattice points corresponding to their desired pharmacophore locations, save the resulting object, and then run STRIFE.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Customization of pharmacophoric points in STRIFE using PyMOL.40 A lattice of points is centered around the fragment exit vector (gray atom). Users select points representing desired pharmacophore locations and save them in an SDF file. Red and blue points represent acceptor and donor points, respectively. STRIFE then attempts to generate elaborations that place matching pharmacophores near these user-specified points.

Model Training

We trained our generative models using a training set derived from a subset of ZINC41 randomly selected by Gómez-Bombarelli et al.6 For each molecule, we generated fragment-ligand pairs by enumerating all acyclic single bond cuts that were not part of functional groups. The resulting training set contained approximately 427,000 examples. We used the same hyperparameters for training as in our previous work.19

Experiments

We evaluated STRIFE’s ability to generate appropriate elaborations using a test set derived from the CASF-2016 dataset.29 This test set was constructed using the same procedure as our training set and initially contained 237 examples. To specifically assess the model’s ability to learn from FHM-derived structural information, we excluded examples where the ground truth molecule was not within an apolar hotspot region and where the hotspots algorithm failed to identify suitable pharmacophoric points. We also filtered examples where STRIFE could not identify any quasi-actives. These filtering steps removed 109, 26, and 1 examples, respectively, resulting in a final test set of 101 examples (listed in Table S1). While these filtering steps removed a substantial portion of the initial test set, the initial set was created by fragmenting ground truth ligands without considering the protein context. Many of these fragments were likely unsuitable for elaboration in a real-world scenario.

Using the STRIFE pipeline (Figure 2), we sampled 250 elaborations for each example in the test set. We compared STRIFE to four baselines:

- Scaffold-Decorator: The deep generative model published by Arús-Pous et al.,17 a SMILES-based, structure-unaware model.

- CReM: A database-based fragment elaboration method.

- DeepFrag: A structure-aware database-based method.

- STRIFENR: A truncated version of STRIFE, performing only the exploration phase (Figure 2a) and omitting the refinement phase, thus generating elaborations from the coarse-grained model without hotspot location information.

We provided CReM with the same 250,000 molecule set used to derive STRIFE’s training sets, converted into a fragment database using CReM’s fragmentation procedure. The Scaffold-Decorator model was trained using the same examples as STRIFE’s generative models. For DeepFrag, we used the pre-trained model provided by the original authors.24 DeepFrag training requires protein-fragment complexes for each example, making it infeasible to train it on the 250,000 ZINC subset.41 DeepFrag is trained on a different chemical space than other baselines, including protein-ligand complexes from CASF-2016, making direct comparison challenging. We include DeepFrag results primarily for completeness and to provide an indication of STRIFE’s performance relative to another structure-aware method.

Evaluation Metrics

For CASF test set experiments, we report standard 2D metrics consistent with our previous work:19

- Validity: Percentage of generated molecules parsable by RDKit42 with at least one atom added to the fragment.

- Uniqueness: Proportion of distinct molecules generated, calculated as (number of distinct molecules) / (total molecules).

- Novelty: Proportion of generated elaborations not present in the model training set.

- Passed 2D Filters: Percentage of generated molecules passing a set of 2D filters. A molecule was filtered if its SAScore43 (synthetic accessibility score) was higher than the fragment’s SAScore, if the elaboration contained a nonaromatic ring with a double bond, or if it failed any pan-assay interference (PAINS)44 filters.

Uniqueness and novelty were not computed for CReM because CReM does not allow specifying a desired number of elaborations. CReM returns a set of “reasonable” elaborations from its database, inherently ensuring uniqueness. As CReM proposes molecules from a fixed vocabulary, none are considered novel. Similarly, novelty and uniqueness were not computed for DeepFrag. For DeepFrag, we attributed 250 elaborations per example by selecting elaborations ranked 1-250 (from a vocabulary of 5000) by DeepFrag’s ranking method.

In addition to 2D metrics, we report a QED-based metric39 to assess the impact of satisfying pharmacophoric points on generating druglike elaborations:

- ΔQED: Average difference in QED between elaborated molecules and the original fragment, calculated as , where .

To evaluate STRIFE’s ability to generate elaborations forming promising interactions, we used constrained docking in GOLD38 to dock each ligand 10 times and calculated the top-ranked pose’s docking score. To mitigate scoring function bias towards larger molecules,45 we calculated ligand efficiency (LE) by dividing the docking score by the number of heavy atoms. To account for score variations across targets, we standardized ligand efficiencies for each example to zero mean and unit variance, applying this transformation to the ground truth ligand efficiency. For the jth example, we compute ΔSLEα,j = SLEα,j – SLEGT,j, where SLEα,j is the average standardized LE of the top α ranked molecules, and SLEGT,j is the standardized LE of the ground truth. If α exceeds the total number of elaborations with computed LE (due to 2D filter exclusion), we use the average SLE of all such molecules. We average over all examples to obtain . ΔSLEα (standardized ligand efficiency improvement) considers only a subset of generated molecules, mirroring real-world fragment-to-lead campaigns where human experts would not inspect hundreds of low-ranked molecules.

As CReM cannot return a fixed number of elaborations, we calculated three sets of summary statistics for CReM, each using a different test set subset. If CReM returned >250 elaborations, we sampled 250:

- Examples with 250 CReM elaborations (n = 45).

- Examples with ≥50 CReM elaborations (n = 62).

- Examples with ≥1 CReM elaboration (n = 82).

Table 1 presents results for the first set. Comparisons across subsets are in Supporting Information (Table S2). Including all examples with ≥1 elaboration degraded ΔSLEα values due to examples with very few proposed elaborations.

Table 1. Comparison of CReM, Scaffold-Decorator, DeepFrag, STRIFENR, and STRIFE on the CASF Test Seta.

| Metric | CReM | Scaffold-Decorator | DeepFrag | STRIFENR | STRIFE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 100% | 99.98% | 100% | 99.5% | 98.96% |

| Unique | N/A | 32.78% | N/A | 56.96% | 37.31% |

| Novel | N/A | 4.23% | N/A | 55.65% | 49.21% |

| Pass 2D filters | 66.06% | 98.2% | 78.47% | 73.81% | 75.38% |

| ΔQED | –0.148% | -0.05% | –0.125% | –0.09% | –0.086% |

| ΔSLE20 | –0.029 | 0.1 | –0.177 | 0.44 | 0.512 |

| ΔSLE50 | –0.489 | –0.222 | –0.56 | 0.078 | 0.164 |

| ΔSLE100 | –0.992 | –0.572 | –0.979 | –0.316 | -0.228 |

[a] See Methods and Evaluation Metrics for metric definitions. Bold indicates the best value across methods.

Results and Discussion

Our evaluation of STRIFE’s ability to propose fragment elaborations by incorporating meaningful pharmacophoric information into the generation process, through large-scale experiments on a CASF-2016 derived test set,29 demonstrates its effectiveness. STRIFE generates a broad range of chemically valid elaborations, many novel to the training set. Crucially, STRIFE substantially outperforms existing computational fragment elaboration methods,17,22 in generating ligand-efficient elaborations, highlighting the advantage of incorporating structural information. We further demonstrate STRIFE’s applicability to real-world fragment-to-lead campaigns through two literature-derived case studies, showcasing its ability to explore design hypotheses, including side-chain movement.

Large Scale Experiments

Our CASF set experiments demonstrate the benefits of incorporating structural information in the generative process (Table 1). All methods generated chemically valid elaborations in >99% of cases, showing their ability to apply valency rules. Scaffold-Decorator,17 a structure-unaware SMILES-based model, generated the lowest proportion of unique molecules (33%). STRIFENR, a truncated STRIFE version omitting hotspot information, generated more unique elaborations (57%) than STRIFE (37%). This is expected, as STRIFE’s refinement phase focuses sampling in a reduced chemical space.

STRIFE demonstrated generalization beyond the training set, with ~49% novel elaborations. In contrast, only 4% of Scaffold-Decorator elaborations were novel, suggesting stronger training set dependence. Scaffold-Decorator elaborations passed 2D filters at a higher rate (98%) than STRIFE (75%) and STRIFENR (74%). This is unsurprising, as Scaffold-Decorator elaborations are mostly from the filtered training set.

STRIFE achieved the second highest ΔQED, behind Scaffold-Decorator, suggesting that satisfying FHM-derived pharmacophoric points did not significantly compromise druglikeness. All methods, on average, proposed “less druglike” molecules than the fragments, which is not unexpected as QED optimization was not a training objective. However, all methods generated a substantial number of more druglike elaborations than the original fragment (Table S3).

On ΔSLE, assessing ligand efficiency improvement over the ground truth, structure-informed models proposed more ligand-efficient elaborations. Considering the top 20 elaborations, CReM (ΔSLE20 = −0.029) and Scaffold-Decorator (ΔSLE20 = 0.1) were, on average, less ligand efficient than the ground truth, unlike STRIFENR (ΔSLE20 = 0.44) and STRIFE (ΔSLE20 = 0.512). This suggests that fine-grained pharmacophoric profiles in STRIFE’s refinement phase enable more ligand-efficient elaborations by placing pharmacophores closer to hotspot points. The trend persisted for top 50 and 100 elaborations, although average ligand efficiency decreased for all models compared to ground truth. ΔSLEα variation with α is shown in Supporting Information (Figure S3).

In terms of the proportion of all generated elaborations exceeding ground truth ligand efficiency, STRIFE achieved the highest (26%), compared to 22%, 17%, and 12% for STRIFENR, Scaffold-Decorator, and CReM (for examples with 250 elaborations), respectively.

Comparison with DeepFrag

Direct comparison with DeepFrag is challenging. DeepFrag training, requiring protein-fragment complexes, may be limited by the scarcity of such structures (Binding MOAD database46 ~40,000 structures), restricting its chemical space compared to other models. On the CASF test set, DeepFrag achieved the lowest ΔSLE20 and ΔSLE50 values and only a better ΔSLE100 than CReM. DeepFrag’s inability to leverage structural information for more ligand-efficient elaborations than structure-unaware Scaffold-Decorator is surprising. Further details on DeepFrag elaborations are in Supporting Information.

Fragment-Based Design of an N-Myristoyltransferase Inhibitor

Rhinovirus, a key pathogen in respiratory diseases like asthma and COPD,47 and cystic fibrosis,48 is supported by host cell N-myristoyltransferase (NMT) for capsid assembly and infectivity, making NMT a potential antiviral target.49,50

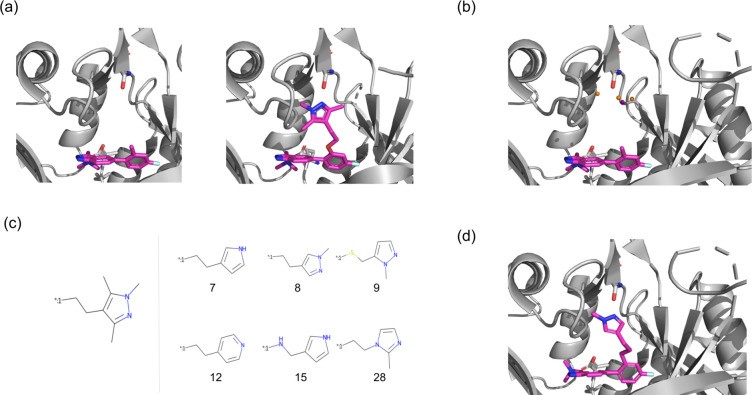

Following a fragment screen against Plasmodium falciparum NMT,51 Mousnier et al.30 identified IMP-72 (Figure 4a), a fragment-like compound with weak activity (IC50 = 20 μM) against human NMT1 (HsNMT1). IMP-72’s binding mode was determined in P. vivax NMT (PvNMT), but key interactions involved conserved residues in human NMTs, making it a viable starting point. IMP-72 bound in a region complementary to quinoline inhibitor MRT00057965,52 but fragment merging was precluded. A simplified quinoline fragment, IMP-358, was constructed to mimic MRT00057965 interactions (S319 in PvNMT, S405 in HsNMT1) without clashing with IMP-72. Despite weak HsNMT1 inhibition (17% at 100 μM), IMP-358 synergistically enhanced IMP-72 potency 300-fold for HsNMT1. IMP-917 was developed by replacing IMP-358 with a trimethylpyrazole group linked to IMP-72 with an ether linker, exhibiting a 1500-fold potency improvement (IC50 = 0.013 μM) and retaining key interactions of both IMP-72 and IMP-358. Modifications to IMP-917’s core demonstrated that NMT inhibition completely prevents rhinovirus replication without cytotoxicity, identifying a drug target.

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Fragment elaboration case study: (a) Left: Crystal structure (PDB ID: 5O48) of fragment IMP-72 bound to P. vivax NMT. Right: Crystal structure (PDB ID: 5O6H) of optimized compound IMP-917 bound to human NMT1. Trimethylpyrazole in IMP-917 interacts with S319. (b) Processed pharmacophoric points from FHM calculated on P. vivax NMT. Orange spheres: acceptor points, purple sphere: donor point. (c) Mousnier et al.’s30 elaboration (left) compared to STRIFE elaborations (right) satisfying the same design hypothesis. Rank assigned by STRIFE is shown below each elaboration. (d) Docked pose of a STRIFE elaboration, showing potential hydrogen bond interaction with S319.

We investigated STRIFE’s ability to propose molecules satisfying Mousnier et al.’s30 design hypothesis. We treated the task as elaboration and sought elaborations interacting with S319, rather than iterative refinement and linker construction. STRIFE input: IMP-72 SMILES, exit vector, and PvNMT crystal structure (PDB ID: 5O48). We used PvNMT due to the lack of IMP-72/HsNMT1 crystal structure, considering NMT conservation across species and preferring PvNMT over docking IMP-72 into IMP-917/HsNMT1 structure. STRIFE generated 250 IMP-72 elaborations, docked using constrained docking in GOLD,38 and ranked by ligand efficiency. Figure 4C shows IMP-917’s added structure and highly ranked STRIFE elaborations potentially interacting with Serine in the same way. Despite only 250 compounds, some STRIFE molecules strikingly resemble Mousnier et al.’s30 trimethylpyrazole elaboration. Unique STRIFE elaborations are in Supporting Information (Figures S6–S10).

Customizability

While structure-aware generative models are emerging, current models typically use static structures, neglecting side-chain movement upon ligand binding. STRIFE, using GOLD’s38 flexible docking, allows exploring design hypotheses involving side-chain movement, illustrated with a literature example.

O’Connell et al.31 developed a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor by elaborating a weak fragment. The first elaboration enabled a hydrogen bond between an appended pyridyl group and Y119A, which moved significantly to accommodate the interaction, improving binding affinity 2500-fold (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Figure 5. Flexible docking visualization using Hermes.35 (a) Fragment (yellow carbons, PDB ID: 6OOY) and elaborated molecule (magenta carbons, PDB ID: 6OOZ) from O’Connell et al.31 Y119A side chain movement to form a hydrogen bond. Orange sphere: user-specified pharmacophoric point input to STRIFE. (b) Example STRIFE-generated molecule satisfying the design hypothesis. Docked into fragment crystal structure (PDB ID: 6OOY, magenta side chain: predicted conformation) using GOLD flexible docking, supporting side-chain movement to accommodate the ligand.

The Y119A side-chain movement poses a challenge for generative models, as predicting such movement is difficult. Even if chemists predict residue movement for hydrogen bonding, communicating this to generative models is not straightforward. STRIFE, while not predicting side-chain movement a priori, can generate molecules satisfying such hypotheses if a human expert anticipates movement. This is achieved by manually specifying a pharmacophoric point (Figure 5a) such that a ligand pharmacophore at those coordinates could interact with the residue if it moved as hypothesized. STRIFE then generates molecules with pharmacophores near the user-specified point and uses GOLD38 flexible docking, allowing residue movement, to dock molecules. Users can then identify high-scoring elaborations predicted to interact with the protein via side-chain movement.

To assess STRIFE’s ability to generate molecules satisfying O’Connell et al.’s31 design hypothesis, we manually specified a pharmacophoric point (Figure 5a) and generated 250 elaborations. To allow GOLD’s genetic algorithm to explore the larger solution space from side-chain flexibility, we generated 100 poses per molecule and used the highest-scoring pose for ligand efficiency calculation. Flexible docking protocol details are in Supporting Information.

STRIFE successfully recovered O’Connell et al.’s31 potent pyridyl elaboration and proposed structural analogs potentially forming similar hydrogen bonds with Y119A. The most common elaboration was a meta-substituted pyridine. 49 of 250 elaborations contained a pyridine substructure, and 125 included an aromatic hydrogen bond acceptor. Pyridine elaborations were not top-ranked by GOLD’s PLP scoring function, which favored pyrazole analogs or hydrophobic elaborations. However, consistent with the crystal structure, both the pyridyl ground truth and highly ranked elaborations predicted Y119A side-chain movement to accommodate the elaboration. Example in Figure 5b. Further elaboration details are in Supporting Information (Figures S11 and S12).

Our analysis relied on manually choosing the pharmacophoric point. To assess STRIFE’s robustness to pharmacophoric point placement, we constructed a lattice of points in the binding pocket (Figure S13) and used each as STRIFE input. As expected, varying pharmacophoric point position affected elaborations. Points closer to the exit vector produced shorter elaborations than distant points (Figure S14).

STRIFE recovered the pyridyl ground truth for 11 of 27 pharmacophoric points, demonstrating robustness to exact placement. More importantly, we assessed how often STRIFE generated elaborations with a pharmacophoric profile equivalent to the pyridyl ground truth. For each pharmacophoric point, we counted elaborations of length 5 or 6 with an aromatic hydrogen bond acceptor and plotted this against exit vector-pharmacophoric point distance (Figure S15). Figure S15 shows that with pharmacophoric points 3-4 Å from the exit vector, STRIFE usually generated a substantial number of elaborations with a pyridyl-like pharmacophoric profile. This indicates STRIFE’s robustness to precise pharmacophoric point placement (not needing exact positioning for sensible elaborations) but also that placement strongly influences generated elaborations.

In summary, despite a small number of elaborations, STRIFE, using pharmacophoric information, generated plausible elaborations satisfying the design hypothesis. Predicting side-chain movement is often difficult, but STRIFE can assess movement plausibility and provide starting points for fragment-to-lead campaigns.

Conclusion

We have presented STRIFE, a fragment elaboration model that incorporates target-derived meaningful information into the generative process. Unlike other fragment elaboration generative models, STRIFE integrates target-specific information without requiring known actives (although active information can be easily incorporated).

Currently, STRIFE uses FHM information to guide hydrogen bond acceptor/donor placement in elaborations. While hydrogen bonds significantly improve binding affinity, they are not the only factor in fragment elaboration. The STRIFE framework could be expanded to explicitly consider hydrophobicity and aromaticity for greater design control. While we used FHMs for protein information extraction, alternative pharmacophore interaction fields like GRAILS53 or T2F54 could provide similar information for the generative model. A current limitation is STRIFE’s lack of simultaneous satisfaction of multiple pharmacophoric points within a single elaboration, potentially limiting efficiency in some cases. However, fragment elaboration campaigns are typically incremental, and STRIFE allows simultaneous targeting of multiple pharmacophoric points (FHM-derived or manual) if desired.

While we used a two-stage exploration-refinement approach, a single-stage approach using many potential pharmacophoric profiles is an alternative. However, our two-stage approach is likely more computationally efficient, as generating elaborations with numerous fine-grained profiles without suitability assessment could lead to docking large numbers of unsuitable molecules.

STRIFE ranks generated molecules by predicted ligand efficiency, calculated via docking score divided by heavy atom count. Docking scores are imperfectly correlated with experimental binding affinities (e.g., ref (29)), but have been used to screen libraries and prioritize compounds for validation55−57, providing useful guidance. Users can easily substitute alternative ranking metrics.

Compared to structure-unaware models, STRIFE has a moderate upfront computational cost for FHM calculation and quasi-active identification (30-60 minutes on a desktop in most cases). However, the most significant computational expense is docking, which is comparable to other methods when generating large sets. Quasi-actives are identified only once per fragment.

While STRIFE can be used with minimal input, user specification is required for fragment and exit vector selection. Fragment library screening may yield many weak hits, producing numerous fragment-exit vector pairs. STRIFE can exhaustively sample each pair, but future research could focus on prioritization schemes for promising starting points to improve resource allocation efficiency.

An advantage of STRIFE’s structural information representation is its interpretability, aiding user understanding of STRIFE’s elaborations and enabling easy specification of user design hypotheses. We hope STRIFE will be useful for both automatic elaboration generation for fragments bound to novel targets and rapid enumeration of elaborations conforming to specific design hypotheses, serving as a basis for further designs.

Data and Software Availability

STRIFE is available for download at https://github.com/oxpig/STRIFE. The default STRIFE implementation requires the commercial CSD Python API for FHM calculation and GOLD constrained docking. Users without CSD Python API access can still use STRIFE by manually specifying pharmacophoric points (see Methods, Customizability) and using alternative docking software. SMILES strings for generative model training and path length model molecules, and structures for large-scale evaluation are available in the STRIFE GitHub repository.

Acknowledgments

T.E.H. is supported by EPSRC, LifeArc, F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, and UCB Pharma (Reference: EP/L016044/1). F.I. is supported by EPSRC and Exscientia (Reference: EP/N509711/1). We thank Mihaela Smilova, Ruben Sanchez-Garcia, Torsten Schindler, Lewis Vidler, Will Pitt, Vladas Oleinikovas, and Garrett M. Morris for helpful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01311.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

ci1c01311_si_001.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ci1c01311_si_001.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)