The journey home after a hospital stay should be a smooth transition towards recovery, but for many patients, the weeks following discharge are fraught with challenges. Hospitals are increasingly focused on enhancing their transitional care practices to address this critical period. The aim is to reduce the concerningly high 30-day readmission rates, minimize adverse events, and ensure that patients experience a safe and effective transition from the structured hospital environment to their homes. Despite growing recognition of the importance of transitional care programs, concrete evidence demonstrating significant reductions in readmission rates, particularly for vulnerable populations such as stroke patients and those with neurological conditions, remains limited. Successful programs often incorporate a “bridging” approach, combining interventions before and after discharge, and rely on dedicated transition providers who are involved at multiple stages of the process. This article will delve into the concept of transition care programs, exploring their key components, effectiveness, and how they can be optimized to improve patient outcomes and healthcare quality.

The period immediately following hospitalization is a vulnerable time for patients. Statistics show that approximately one in five patients experience adverse events during this phase, ranging from adverse drug events (ADEs) to hospital-related complications.[1-3] Alarmingly, readmission to the hospital is a common occurrence. Nearly 20% of older Medicare patients are readmitted within 30 days of discharge.[1] This revolving door of hospitalizations not only impacts patient well-being but also places a significant strain on healthcare systems.

A wide array of adverse events can manifest post-discharge, encompassing diagnostic and therapeutic errors. However, ADEs stand out as particularly prevalent and detrimental, frequently leading to further hospitalizations and readmissions.[4, 5] Recent studies indicate that almost 100,000 elderly patients are hospitalized annually due to ADEs.[6] Patients who have experienced a stroke are particularly vulnerable. They face a heightened risk of recurrent cerebrovascular events, repeat hospitalizations within a year of their initial admission, increased levels of disability, and higher mortality rates.[7, 8] For neurohospitalists, ensuring safe care transitions for patients with complex, chronic neurological illnesses such as stroke, demyelinating diseases, epilepsy, and neuromuscular conditions is a crucial aspect of patient safety.[9]

Transitional care, fundamentally, is the care patients receive as they navigate the shifts between different healthcare settings and providers. It’s about effectively “bridging” the gaps in care that can arise when moving between hospitalizations and outpatient visits.[10, 11] Hospital-based transitional care interventions are specifically designed to make the transition from the inpatient to the outpatient setting as seamless as possible, thereby preventing unnecessary readmissions and adverse events.

National policy initiatives are increasingly emphasizing improvements in transitional care, driven by the substantial costs associated with adverse events and readmissions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) already publicly reports hospitals’ risk-adjusted 30-day readmission rates for conditions like pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure (CHF).[12] It is anticipated that this reporting will expand to include neurological conditions such as stroke in the near future.[13] Recognizing the financial burden of readmissions, CMS has implemented penalties for hospitals with high readmission rates, with over 2,000 hospitals facing potential reductions in Medicare reimbursements.[14] The Partnership for Patients initiative, aiming to reduce preventable readmissions by 20%, highlights improved transitional care as a key strategy for lowering healthcare expenditures.[15] Collectively, these policies underscore a clear mandate for hospitals to prioritize and improve transitional care for patients upon discharge.

While highly focused, disease-specific transitional care strategies have shown some success in reducing readmissions for conditions like CHF, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma, effective strategies for neurological diseases are less well-defined. Systematic reviews have identified various interventions under study,[16-19] but the impact of these interventions on readmissions and other post-discharge patient safety indicators, such as emergency department (ED) visits and adverse events, needs further investigation.

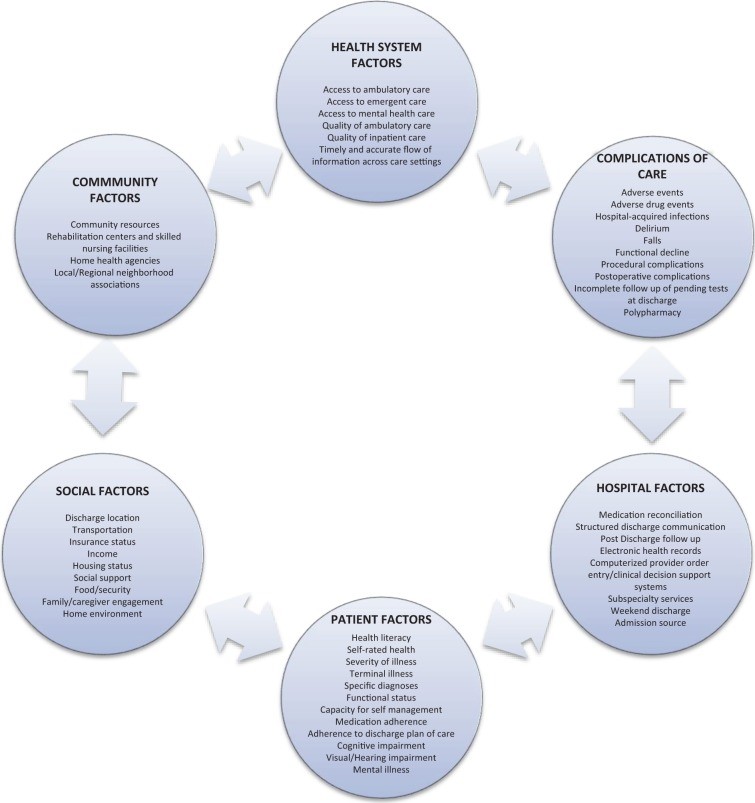

Data suggests that nearly 20% of 30-day readmissions are potentially preventable, based on studies analyzing readmission risk factors.[20] Hospital readmission rates are often influenced by factors beyond the hospital walls, including limited social support, socioeconomic factors, and access to outpatient care (Figure 1).[21-23] A retrospective review of stroke and cerebrovascular disease discharges from a single academic medical center revealed that a significant 53% of readmissions were potentially avoidable. These avoidable readmissions were linked to issues such as gaps in care coordination, delayed follow-up appointments, and inadequate discharge instructions.[24] Despite these ongoing challenges, progress is being made. CMS has reported a decline in 30-day readmission rates for Medicare patients between 2007 and 2012, indicating a positive trend in readmission prevention efforts.[25]

Figure 1. Factors Contributing to Hospital Readmission

Figure 1: Key determinants influencing hospital readmission rates, encompassing both patient-specific and system-level factors.

In an era focused on value-based healthcare and cost-effective solutions, transitional care strategies stand out as crucial. While effective implementation requires dedicated human resources, these strategies align with the core priorities of neurohospitalists and the needs of patients: enhancing the quality of care, prioritizing patient safety, and fostering better connections within the healthcare ecosystem. This review will explore various transitional care strategies, examine the effectiveness of established programs, and provide actionable recommendations for neurohospitalists seeking to improve patient transitions.

Deconstructing Transitional Care: Definitions, Risks, and Strategic Approaches

Defining Transitional Care Strategies and Post-Discharge Adverse Events

A “transitional care strategy” can be defined as a planned intervention, or a combination of interventions, initiated before a patient leaves the hospital. The overarching goal is to ensure a safe and effective transition as patients move from one healthcare setting to another, most commonly from the hospital back to their home. These interventions are often categorized into three main types: predischarge interventions (actions taken before the patient is discharged), postdischarge interventions (actions taken after the patient leaves the hospital), and “bridging” interventions (which incorporate components from both pre- and postdischarge phases; Table 1).[17, 26-30]

Table 1. Taxonomy of Interventions for Enhanced Transitional Care at Hospital Discharge

| Category of Intervention | Specific Intervention Examples |

|---|---|

| Predischarge Interventions | Risk assessment for adverse events or readmissions |

| Patient and caregiver engagement and education | |

| Creation of a personalized patient health record in easy-to-understand language | |

| Proactive communication with outpatient healthcare providers | |

| Multidisciplinary discharge planning teams | |

| Assignment of a dedicated transition provider for pre- and post-discharge contact | |

| Medication reconciliation | |

| Postdischarge Interventions | Patient outreach initiatives (follow-up calls, hotlines, home visits) |

| Facilitation of timely clinical follow-up appointments | |

| Post-discharge medication reconciliation | |

| Bridging Interventions | Strategies incorporating at least one predischarge and one postdischarge component |

Postdischarge adverse events encompass a range of negative patient experiences that represent clinically significant harm occurring after hospital discharge. These can include: the emergence of new symptoms or the worsening of existing ones, abnormal laboratory results requiring changes in clinical management, and injuries (such as ADEs, falls, or hospital-acquired infections) that are at least partly attributable to the care received during hospitalization. This definition is consistent with classifications used in previous studies analyzing the prevalence and nature of postdischarge adverse events.[3, 4] In medical research, readmission to the hospital is frequently considered a significant adverse event and is often measured at various intervals, such as 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, and 6-month readmission rates from the initial hospitalization.

Identifying the Risk: Who is Vulnerable to Readmission and Adverse Events?

Predicting with certainty which patients will be readmitted or experience an adverse event after discharge remains a challenge. However, certain patient groups are demonstrably at higher risk during the post-hospitalization period. These include older adults, individuals with chronic illnesses, and those hospitalized for conditions like stroke. This increased risk stems from factors such as fragmented healthcare delivery, transitions across multiple care settings, and frequent handoffs between different providers.[1, 3, 17, 31-33] Research has identified several specific risk factors for hospital readmission and poorer outcomes in neurologic patients, including poor functional status at discharge, advanced age, the presence of psychiatric illness, and limited access to social support services.[34-36] Interestingly, a systematic review evaluating predictors of readmission following stroke found that there are no consistently reliable risk-standardized models to predict readmissions across different hospitals.[37]

Despite the absence of standardized prediction models, older adults and individuals with multiple chronic conditions constitute a significant proportion of admissions and readmissions within inpatient neurology services. Stroke patients, in particular, are frequently readmitted for a variety of reasons, including cerebrovascular issues, cardiac conditions, and non-cardiac conditions such as urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and hip fractures.[8, 38, 39]

Exploring Effective Transitional Care Strategies

Several transitional care strategies have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing readmissions in controlled trials. Four prominent strategies are highlighted below (Table 2), chosen based on evidence from published studies showing their positive impact on readmission rates.

Table 2. Spotlight on Effective Hospital-Based Transitional Care Programs

| Program Name | Core Strategies | Program Description and Effectiveness Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Care Transitions Intervention (CTI)[40-43] | Patient engagement, individualized patient record, dedicated transition provider, communication facilitation with outpatient providers, outreach, medication reconciliation | Focuses on four key domains of self-management skills. Extensively studied across various healthcare settings. Demonstrated significant reductions in 30-day readmission rates (Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) ranging from 3.6% to 5.8% in different studies) and 90-day readmission rates (ARR 5.8% to 21.7%). Showed non-significant reduction in 30-day ED visits in one study (ARR 3.2%, NS). |

| Transitional Care Model (TCM)[44-47] | Patient engagement, individualized patient record, dedicated transition provider, communication facilitation with outpatient providers, facilitated clinical follow-up, outreach | Nurse-led program specifically designed for geriatric patients, emphasizing intensive outreach with home and telephone follow-up. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown significant decreases in 90-day readmission rates (ARR ranging from 13% to 48% in different studies, measured at different time points post-discharge). ED visits within 24 weeks were not significantly reduced in studies (NS). One study showed a non-significant reduction in post-discharge infections (ARR 16.7%, NS). |

| Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED)[48] | Patient engagement, individualized patient record, dedicated transition provider, communication facilitation with outpatient providers, multidisciplinary team approach, outreach, medication reconciliation (pre- and post-discharge) | Team-based program incorporating pharmacist outreach and comprehensive medication reconciliation. RCTs demonstrated a non-significant reduction in 30-day readmission rates (ARR 5.8%, NS), but a significant reduction in 30-day ED visits (ARR 8.0%). |

| Project Better Outcomes for Older Adults Through Safe Transitions (BOOST)[49-52] | Patient engagement, multidisciplinary team approach, outreach, medication reconciliation, risk assessment | Multicenter quality improvement (QI) program with mentored implementation across hospitals. Clinical controlled trials (CCTs) and pre-post studies have shown reductions in 30-day readmission rates (ARR 2% to 5.9%). |

Care Transitions Intervention (CTI)

The Care Transitions Intervention (CTI), developed by Dr. Eric Coleman at the University of Colorado, is a multi-faceted program implemented in numerous hospitals.[40-43] Studies have included older adults hospitalized with stroke and various chronic illnesses. The core objectives of the CTI are to actively engage patients and empower them and their caregivers to participate in self-management after discharge. This includes equipping them with the necessary skills to effectively navigate the healthcare system. CTI is built upon four key pillars: (1) medication management, ensuring patients understand and can manage their medications; (2) personal health record development, creating a portable record for patients to use across different care settings; (3) proactive follow-up with a primary care provider; and (4) identification of “red flags” – symptoms or situations that should prompt patients to contact their healthcare providers. A “transition coach,” typically an advanced practice nurse, conducts post-discharge home visits and telephone calls, reinforcing patient engagement and self-management strategies for chronic conditions. This program has been evaluated in diverse acute care settings, consistently demonstrating statistically significant reductions in 30-day readmissions across managed care systems, capitated delivery systems, and Medicare fee-for-service populations.

Transitional Care Model (TCM)

The Transitional Care Model (TCM), pioneered by Dr. Mary Naylor at the University of Pennsylvania, is another nationally recognized program. TCM focuses on hospital-based discharge planning and home follow-up, primarily targeting chronically ill, high-risk older adults, including those with CHF and myocardial infarction.[44-47] While studies haven’t specifically highlighted neurologic diagnoses, the principles are broadly applicable. In TCM, a transitional care nurse (TCN) guides patients from the hospital to their home environment, facilitating communication between inpatient and outpatient providers. The TCN conducts a series of home visits and follow-up phone calls in the post-hospitalization period. TCM emphasizes a multidisciplinary approach, with the TCN acting as a central coordinator, maintaining communication with physicians, nurses, social workers, discharge planners, and pharmacists. Multiple studies have demonstrated significant reductions in readmission rates at both 60 and 90 days post-discharge.

Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED)

Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) was studied within a general medicine population at an urban safety-net hospital. It emphasizes a multidisciplinary approach to patient care, coordinated by a nurse discharge advocate (DA).[48] The DA engages with patients throughout their hospitalization, providing crucial clinical information and a personalized, easy-to-understand post-hospitalization plan. After discharge, a pharmacist conducts telephone follow-up, including a thorough medication review and direct communication with the patient’s primary outpatient provider. The initial Project RED study, while not specifically focused on neurologic patients, showed significant improvements in hospital utilization, defined as combined ED visits and readmissions, within 30 days of discharge. Hospital utilization was reduced by approximately 30% in the study population.

Project Better Outcomes for Older Adults Through Safe Transitions (BOOST)

Project Better Outcomes for Older Adults Through Safe Transitions (BOOST) is a transitional care program supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine.[49-52] This quality improvement collaborative has been implemented across a wide range of US hospitals, targeting general medicine populations, encompassing both medical and medical-surgical patients. BOOST utilizes mentors, hospitalist experts in quality improvement and transitional care, to guide hospitals in developing and implementing site-specific programs tailored to their unique needs. The BOOST toolkit offers various interventions, including risk assessment tools, medication reconciliation processes, discharge checklists, and strategies for fostering a multidisciplinary team approach to discharge planning. A study of 30 hospitals implementing BOOST showed modest reductions in readmission rates, although data was only available from 11 hospitals in the study.[51]

Tailoring Strategies for Neurologic Patients

Several studies have specifically investigated the effectiveness of transitional care programs designed for stroke patients. A systematic review of 27 transitional care studies for acute stroke patients concluded that while a limited number of studies provided low to moderate evidence that hospital-initiated interventions improved certain outcomes – such as reducing hospital stay duration and improving physical activity – they did not demonstrate a significant impact on readmissions or mortality.[34] Despite the lack of conclusive evidence regarding healthcare utilization or adverse event reduction in these studies, the authors highlighted the importance of hospital-initiated strategies focused on care coordination as critical determinants of improved healthcare for stroke patients. Specific interventions, such as implementing secondary stroke prevention measures (antithrombotic, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering agents), screening for dysphagia, and reducing the use of urinary catheters in hospitals, have been shown in various studies to effectively reduce readmissions and post-discharge adverse events like recurrent stroke, pneumonia, and catheter-associated urinary tract infections.[53-59] Neurohospitalists are uniquely positioned to directly influence patient care beyond the hospital stay by implementing interventions that enhance care quality, reduce healthcare costs, and mitigate the risks associated with preventable readmissions and adverse events.

Common Threads in Effective Transitional Care

A key observation across these successful programs is their shared characteristics. Both general programs and many stroke-specific programs incorporate “bridging” interventions, utilizing a dedicated transition provider, often a nurse or case manager, as the clinical leader. There’s a consistent emphasis on having a patient advocate who facilitates care coordination and proactively reaches out to patients after they leave the hospital. Similar to general medicine populations, neurologic patients benefit significantly from strategies that prioritize improved communication across care settings, proactive outreach, and active patient engagement.

Navigating Implementation and Cost Considerations

While descriptions of transitional care programs often detail timelines and interventions, information regarding the costs, resources required for implementation, and strategies for ensuring long-term sustainability is often lacking. Understanding these practical aspects is crucial for successful adoption and widespread implementation of these programs.

Discussion: Key Takeaways on Transition Care Programs

This review has provided a framework for understanding transitional care strategies aimed at decreasing hospital readmissions and post-discharge adverse events, highlighting four nationally recognized programs as examples. A consistent feature of successful transitional care programs over the past two decades is the inclusion of bridging interventions, typically led by a dedicated transition provider who maintains contact with patients both before and after hospital discharge. Programs like CTI, Project BOOST, and TCM have been successfully implemented and rigorously evaluated across diverse patient populations and healthcare systems. Project RED, with a similar approach, has demonstrated success in a safety-net system. While these strategies are resource-intensive, requiring dedicated personnel and infrastructure, evidence suggests they are effective in improving patient outcomes. However, more comprehensive data on implementation processes, long-term sustainability, and detailed cost analyses are still needed. Further research is also necessary to specifically assess the impact of these strategies on patients with acute neurological illnesses.

Recommendations for Neurohospitalists: Actionable Steps to Enhance Transition Care

Hospitals and neurohospitalists are increasingly challenged to optimize post-discharge care to reduce readmissions and avoid associated financial penalties. Research in this area consistently points towards the effectiveness of multidisciplinary, multi-component strategies that utilize bridging interventions and involve a dedicated transitions clinician. Programs like CTI, TCM, Project RED, and Project BOOST serve as valuable models, having been studied and replicated across the US. It’s crucial to recognize that each hospital network has unique internal factors, organizational culture, community context, and geographical considerations. Therefore, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to transitional care is unlikely to be optimal. However, the core elements of a successful transitional care strategy consistently include: patient engagement, the use of a dedicated transitions provider, robust medication management (including medication reconciliation), proactive communication with outpatient providers, and consistent patient outreach (Table 3). For neurology patients, disease-specific interventions can be integrated into these core strategies, such as tailored home care protocols for disease monitoring, medication adherence support, symptom management guidelines, and seamless communication with rehabilitation programs.

Table 3. Key Recommendations for Neurohospitalists to Improve Transition Care

| Actionable Recommendation | Description |

|---|---|

| Analyze Hospital Readmission Data | Obtain comprehensive data on 30-day readmission rates, including all-cause and disease/unit-specific rates, to understand the current landscape and identify areas for improvement. |

| Assess Hospital Infrastructure | Evaluate the hospital’s existing quality improvement and patient safety infrastructure, including the electronic health record system and prior experience with quality improvement initiatives, to leverage existing resources. |

| Build an Interdisciplinary Team | Create a dedicated interdisciplinary team and identify champions within different departments to drive the transitional care program and ensure buy-in and collaboration. |

| Define Measurable Outcomes | Clearly define key outcomes to measure the program’s success, such as 30-day readmission rates, adverse drug events, and medication errors, enabling data-driven improvements. |

| Implement a Bundled Strategy | Implement a comprehensive, multi-component strategy that includes patient engagement, a dedicated transitions provider, medication reconciliation, facilitated communication, and proactive patient outreach, addressing multiple facets of transitional care. |

| Incorporate Disease-Specific Interventions | Integrate disease-specific interventions tailored to the neurology patient population, such as secondary stroke prevention protocols and dysphagia screening, to address specific needs. |

Neurohospitalists, in their roles as both primary providers and consultants, are uniquely positioned to lead and contribute to efforts aimed at improving transitional care for a wide range of patients. For instance, neurohospitalists can spearhead initiatives focused on specific neurological conditions, such as implementing delirium and dysphagia screening protocols for patients with cerebrovascular and neurological diseases. They can also collaborate with medicine hospitalists on broader, institution-wide transitional care strategies. [60-62] As consultants, neurohospitalists can provide evidence-based recommendations to reduce the risk of readmission and adverse events, such as emphasizing secondary stroke prevention measures.

In light of the robust body of research supporting transitional care and the critical importance of enhancing care quality and preventing avoidable readmissions, several practical recommendations should be consistently applied to all patients admitted under the care of a neurohospitalist:

- Patient Engagement: Prioritize patient engagement, including thorough counseling on medication management, recognizing “red flag” symptoms, understanding disease-specific management strategies, and accessing available resources for post-discharge support.

- Communication with Outpatient Providers: Ensure seamless communication with outpatient providers, including rehabilitation facilities and skilled nursing facilities, to guarantee appropriate follow-up appointments, medication reconciliation, and ongoing management.

- Proactive Outreach: Implement proactive outreach mechanisms, such as follow-up telephone calls or home visits when appropriate, to ensure a safe and supported transition for patients in the immediate post-discharge period.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: All statements expressed in this work are those of the authors and should not in any way be construed as official opinions or positions of the University of California, San Francisco, AHRQ, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Stephanie Rennke is a consultant for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Project BOOST.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services (contract no. HHSA-290-2007-10062I).