Palliative care has consistently demonstrated its profound impact on enhancing the quality of life for patients facing serious illnesses, effectively managing distressing symptoms, and optimizing the overall quality of care. Beyond patient benefits, it also contributes to healthcare efficiency by mitigating aggressive and often futile end-of-life interventions, leading to significant cost reductions. Communicating these advantages to the public, healthcare administrators, payers, and government bodies should be straightforward. Indeed, advocating for the development of palliative care services requires a clear, concise, and compelling presentation of both the clinical and financial rationale for the services a palliative care team aims to provide. This guide explores various palliative care program models, including consultation services, outpatient programs, and inpatient units, and outlines crucial components, practical screening tools, the composition of an effective consultation team, a model medical record to facilitate optimal palliative care practices, and essential data metrics for program evaluation.

1. Understanding the Foundations of Palliative Care

At its core, palliative care is defined by a patient-centered approach focusing on comprehensive symptom management, fostering open and honest communication regarding the patient’s condition and prognosis, and collaboratively establishing medically appropriate goals of care. A hallmark of palliative care is its interdisciplinary nature, bringing together nurses, social workers, chaplains or clergy, pharmacists, physicians, and other specialists as equal partners in the patient and family’s care journey. Robust evidence indicates that palliative care significantly improves patient outcomes without causing harm. Reviews by leading experts such as Higginson, Zimmerman, Bruera, and Temel, alongside the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Provisional Clinical Opinion, consistently underscore these positive impacts. While the precise mechanisms through which palliative care achieves these improvements are still being explored, certain core elements are recognized as indispensable for effective program implementation.

This guide aims to elucidate the essential components of palliative care programs and offer practical guidance for effective resource management. The insights presented are drawn from over two decades of collective experience in developing and sustaining palliative care units, incorporating the wisdom of pioneers in the field, including Diane Meier MD, MaryAnn Hager RN MSN, and Laurel Lyckholm RN MD.

2. Choosing the Right Palliative Care Program Model

Determining the optimal setting and model for palliative care delivery is a crucial first step. Currently, limited data directly compares the effectiveness of different program types. The Center to Advance Palliative Care Curriculum Palliative Care Leadership Program has developed a valuable tool to assist in selecting appropriate palliative care and staffing models. Their findings categorize palliative care programs into three primary models:

- Inpatient Consult Services: Teams primarily provide consultations within the hospital setting.

- Inpatient Units (IP Units): Dedicated units within the hospital exclusively for palliative care, potentially alongside consult services.

- Outpatient Clinics: Palliative care services are delivered in an outpatient clinic setting.

Each model presents distinct advantages and disadvantages, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Palliative Care Program Models

| Model Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Consult Service and/or Outpatient Clinic | – Quick program launch with minimal initial staff – Facilitates interdisciplinary collaboration across the entire healthcare system – Relatively low operational costs – Enables hospital-wide palliative care education – Demonstrated increase in appropriate hospice referrals (from 1% to approximately 30% in one study, and 25% to 47% in another) |

– Typically limited to daytime coverage – Potential lack of control over patient care, leading to inconsistent implementation of recommendations (some programs report only 20% adherence to suggestions) – May not achieve significant cost savings due to limited ability to influence patient care pathways or location (e.g., preventing ICU transfers) – Data collection and tracking can be challenging without dedicated financial personnel – Patients transitioning from palliative care to hospice may, in some cases, incur higher costs compared to standard patients |

| Inpatient Unit | – Dedicated palliative care staff ensures specialized and consistent high-quality care – Centralizes expertise and can foster a strong palliative care identity within the hospital – Direct control over patient care within the unit facilitates comprehensive management |

– Potential for reduced palliative care engagement from other hospital departments, as expertise is concentrated in the unit – Requires 24/7 comprehensive care coverage – Some physicians may be reluctant to relinquish primary control of their patients – Must adhere to standard hospital census and budgetary requirements – Risk of being perceived as a “death unit” or a sign of treatment failure by some – Potential misconception of withholding disease-specific treatments, such as feeding tubes, despite palliative care’s focus on holistic well-being – Dedicated expert care, while beneficial, needs to be carefully managed to ensure cost-efficiency |

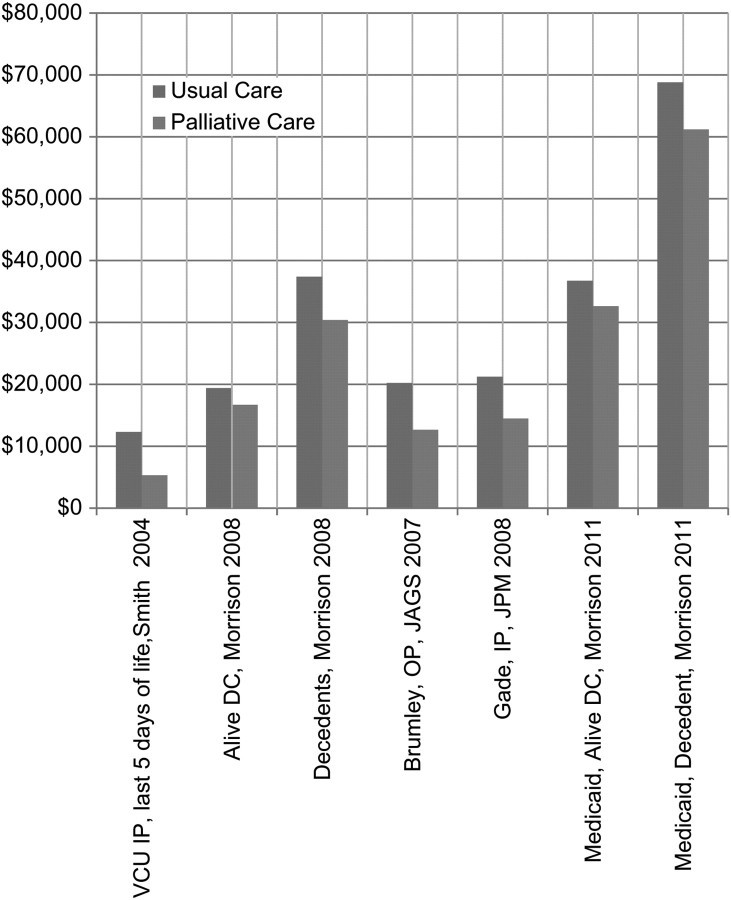

Inpatient Palliative Care Units (PCUs) function similarly to Intensive Care Units, but specialize exclusively in palliative care. They boast dedicated nursing staff, specialized training programs, and tailored protocols. PCUs offer the advantage of providing highly focused care, facilitating specialized procedures like lidocaine or ketamine infusions, and establishing a visible hub for palliative care training, research, and philanthropic activities. However, PCUs operate as cost centers with specific budgetary constraints and performance expectations, such as maintaining a minimum occupancy rate (e.g., 75%) and achieving financial sustainability. Importantly, accumulating evidence consistently demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of palliative care, as illustrated in Figure 1, with typical savings ranging from US$5,000 to $7,500 per case.

Figure 1. Impact of Palliative Care on Healthcare Costs

Figure 1: Visual representation of the cost savings associated with palliative care across various healthcare settings, including Virginia Commonwealth University Inpatient (VCU IP), patients discharged alive (Alive DC), patients who died in the hospital (Decedents), outpatients (OP), and inpatients (IP).

Consult services represent the most readily implementable and maintainable program model. These services require healthcare professionals to assess patients and deliver palliative care interventions. While the interdisciplinary team approach is considered ideal, research by Muir et al. suggests that even a focused team comprising a physician and an advanced practice nurse can yield significant improvements in symptom management within oncology settings. Their model, driven by US reimbursement structures favoring physicians and nurses, demonstrated a 21% reduction in symptom burden, increased oncologist satisfaction (crucial for program sustainability through oncologist collaboration), and a substantial 87% increase in consult volume within two years. This efficiency also translated to time savings for oncologists, freeing up over four weeks annually per oncologist for core oncology practice. While reimbursement for chaplains and psychologists can be challenging, and often requires philanthropic support, their contributions are invaluable and highly appreciated by patients and families, enhancing the holistic nature of palliative care. For a comprehensive review of oncologist-palliative care collaborations, refer to Alesi et al.

The operational scope of a consult service can vary depending on local practices and institutional culture. Some services primarily offer recommendations, while others assume direct patient care responsibilities, including order writing and on-call duties. A recommendation-based model is simpler to initiate and sustain due to its less intensive and long-term commitment. However, its impact on changing established practices, particularly initially, might be limited, potentially missing opportunities for care standardization and associated cost efficiencies. Conversely, the ‘assume care’ model necessitates greater staffing resources to manage complex patients and ensure round-the-clock coverage. Yet, it offers a more robust platform for establishing standardized, medically sound, and cost-effective care pathways. Programs aiming to integrate palliative care earlier in the disease trajectory, such as during active chemotherapy or heart failure management, will require more extensive resources compared to programs focused primarily on end-of-life care.

Direct comparative evidence between consultation programs and inpatient palliative care units is scarce. A study by Casarett et al. involving 10,633 surviving caregivers within the US Veterans Administration system (with a 50–65% response rate) provides valuable insights. Caregivers of patients receiving standard care reported lower satisfaction with end-of-life care compared to those who received palliative care consultations. Satisfaction levels were highest among caregivers of patients admitted to inpatient palliative care units. Furthermore, palliative care consultation and IP unit exposure were associated with increased and earlier implementation of “do not resuscitate” orders, more frequent chaplain visits, and more comprehensive goals-of-care discussions. This suggests a potential dose-response relationship – greater palliative care integration correlates with more effective palliation.

3. Essential Components of a Successful Palliative Care Program

Several key components contribute to the effectiveness of a palliative care program. These include utilizing screening tools for appropriate consults and admissions, employing clinical guidelines and standardized algorithms, implementing a standardized consultation note, and tracking relevant performance metrics for ongoing evaluation.

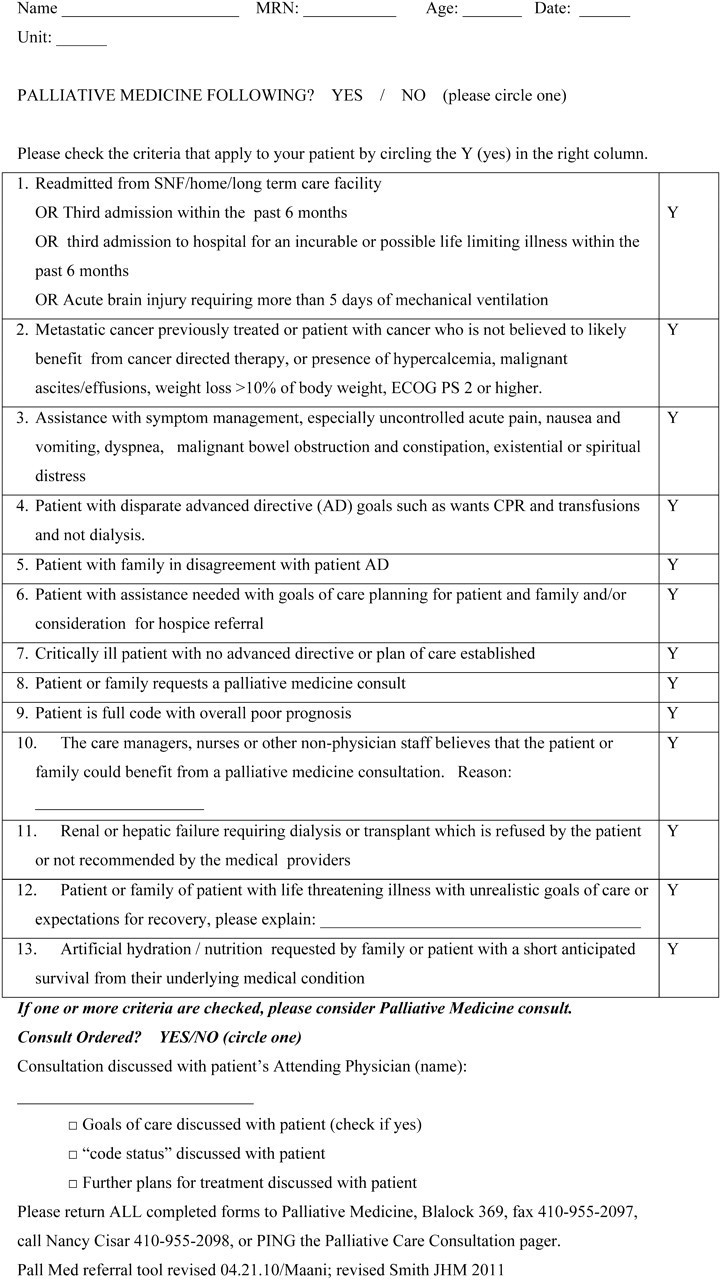

Excellent palliative care screening tools are readily accessible on the Center to Advance Palliative Care website. A modified version of the Geisenger Clinic Form is a practical example (Figure 2). Numerous algorithms designed to optimize care delivery are also freely available on the CAPC website and can be adapted to suit local needs.

Figure 2. Johns Hopkins Medicine Palliative Medicine Consult Worksheet

Figure 2: Example of a Palliative Medicine Consult Worksheet used at Johns Hopkins Medicine, adapted from the Geisenger Health System form developed by Dr. Neil Ellison and colleagues. This tool aids in standardized patient assessment and referral processes.

The National Consensus Project guidelines have been instrumental in improving palliative care delivery in various settings, notably in the study by Temel et al. focusing on non-small cell lung cancer. This study demonstrated improved palliation and a statistically significant 2.7-month increase in survival among patients receiving early palliative care. A modified version of these guidelines, emphasizing pre-prognosis discussion with the referring physician, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Suggested Components of a Palliative Care Consultation

| Key Consultation Area | Specific Inquiries and Actions |

|---|---|

| Understanding of Illness and Goals of Care | – Assess Illness Understanding: “What do you want to know about your illness? What do you currently understand about your situation?” – Clarify Treatment Goals (with Attending Physician Consent): “Would you be open to discussing what might lie ahead?” – Address Adaptation to Changing Goals: Recognize that adapting to evolving goals and the prospect of mortality is an ongoing process, not a one-time conversation. (Personal Communication: Anthony Riley, MD, January 2012) |

| Uncontrolled Symptoms | – Utilize Symptom Assessment Tools: Employ validated tools such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) or the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Symptom Assessment Scale. – Specifically Address: Pain, Pulmonary symptoms (cough, dyspnea), Fatigue and sleep disturbance, Mood (depression and anxiety), Gastrointestinal issues (anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, constipation). |

| Decision Making | – Inquire about Decision-Making Preferences: Understand the patient’s and family’s preferred approach to medical decision-making. – Facilitate Treatment Decisions: Provide support and guidance in navigating complex treatment choices, as needed. |

| Coping with Life-Threatening Illness | – Assess Coping Mechanisms: “This must be incredibly challenging for you and your family. How are you both coping with this illness?” – Consider Support Needs: Evaluate the coping strategies of both the patient and family/caregivers. |

| Referrals and Prescriptions | – Develop a Future Care Plan: Clearly outline and document the care plan for subsequent appointments and follow-up. – Coordinate Referrals: Facilitate referrals to other relevant healthcare providers, ensuring direct communication via fax, email, or electronic medical record. – Document New Medications: Record any newly prescribed medications. |

Table 2: Modified components of a palliative care consultation, adapted from the National Palliative Care Consensus Guidelines (2009). Emphasizes patient-centered communication and comprehensive symptom assessment.

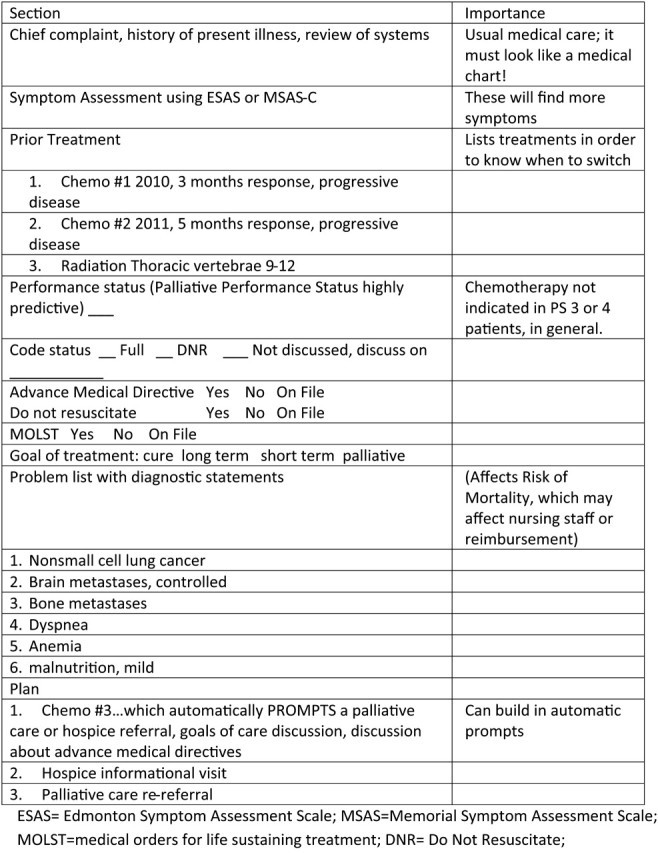

Standardized medical notes incorporating prompts can significantly enhance the completeness and consistency of palliative care documentation. Prompts have been shown to be effective tools in improving clinical practice. For instance, prompts related to advance medical directives can increase the frequency of related discussions. In oncology, prompts can guide clinicians in recognizing when to transition away from aggressive treatments like chemotherapy, particularly after multiple lines of therapy (e.g., three lines for non-small cell lung cancer). Despite evidence suggesting that continued chemotherapy in the last weeks of life offers minimal benefit, a significant proportion of patients (10%–30%) still receive it during this period. Standardized notes with prompts can help initiate timely discussions about palliative care and goals of care. An example of such a note template is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Template of a Note to Enhance Oncology-Specific Palliative Care Information Recording

Figure 3: Example template of a medical note designed to promote comprehensive documentation of palliative care information, specifically within oncology settings. Utilizes prompts to ensure key aspects of palliative care are addressed and recorded.

Programs should proactively monitor their performance using standardized metrics for both internal quality improvement and external benchmarking. Weissman and Meier have proposed a set of standardized metrics, adapted and presented in Table 3, which can be used for this purpose. Analyzing this data provides valuable insights into program reach, referral patterns, and areas for targeted outreach and marketing efforts.

Table 3. Data to Gather for Palliative Care Program Performance Analysis

| Data Element | Rationale for Collection |

|---|---|

| Patient ID | Unique identifier for patient tracking. |

| Patient Age, Gender, Race/Ethnicity | Demographic data to assess program reach across diverse populations. |

| Palliative Care Diagnoses | Categorization of primary diagnoses to understand patient populations served. |

| Referring Service and/or Referring Physician | Identifies referral sources to optimize outreach and education efforts. |

| Date of Hospital Admission | Essential for length-of-stay calculations and impact analysis. |

| Date of Hospital Discharge | Essential for length-of-stay calculations and impact analysis. |

| Date of PCU Admission (if applicable) | Tracks utilization of inpatient palliative care units. |

| Disposition: Inpatient Death vs. Discharge; Discharge Location | Outcomes data, including mortality and discharge destinations (e.g., home, hospice). |

| Hospice Admissions/Discharges | Measures integration with hospice services and referral effectiveness. |

| Patient Billing Status: Acute Care or Hospice Pass-Through | Financial data for reimbursement and cost analysis. |

| Financial Analysis of the Program | Comprehensive evaluation of program profitability, cost avoidance, financial sustainability, and philanthropic support. |

Table 3: Recommended data elements for palliative care programs to collect and analyze, enabling performance evaluation, benchmarking, and targeted improvement initiatives. Adapted from Center to Advance Palliative Care Metrics.

4. Building an Effective Palliative Care Team

The interdisciplinary team is the cornerstone of palliative care. A successful program relies on the expertise and collaborative spirit of various professionals, including:

- Physicians: Provide medical leadership, symptom management expertise, and overall patient care coordination.

- Nurses: Offer skilled symptom management, emotional support, patient and family education, and care continuity.

- Social Workers: Address psychosocial needs, provide counseling, connect patients and families with resources, and assist with discharge planning.

- Chaplains/Clergy: Offer spiritual and emotional support, address existential concerns, and facilitate connections with faith communities.

- Pharmacists: Optimize medication management, provide drug information, and ensure safe and effective symptom control.

- Other potential team members: May include psychologists, dietitians, physical therapists, and occupational therapists, depending on program scope and patient needs.

Effective team functioning hinges on clear roles and responsibilities for each member, fostering open communication, and establishing regular interdisciplinary team meetings to collaboratively develop and adjust patient care plans.

5. Financial and Resource Management

Demonstrating the financial benefits of palliative care is crucial for securing administrative support and program sustainability. As evidenced in Figure 1, palliative care consistently demonstrates cost-effectiveness through reduced hospital readmissions, shorter lengths of stay, and decreased utilization of expensive, aggressive end-of-life care. Presenting this financial data, alongside the compelling clinical benefits, to hospital administrators and payers is essential for advocating for resource allocation and program expansion.

Resource allocation should be strategically aligned with the chosen program model and patient population. Inpatient units typically require more significant upfront investment and ongoing operational costs compared to consult services. Sustainability strategies may involve a combination of hospital funding, insurance reimbursement, and philanthropic contributions. Highlighting the “goodwill” generated by palliative care programs – improved patient satisfaction, enhanced hospital reputation, and community support – can also strengthen the case for resource investment.

Conclusion

Palliative care is not only a rapidly expanding medical specialty but also an essential component of a high-quality, patient-centered healthcare system in any country. It demonstrably improves patient care and outcomes while offering significant cost savings. This guide has outlined key strategies for structuring effective palliative care programs and highlighted tools to enhance service delivery. While ongoing research is needed to further refine program models and optimize efficiency, numerous evidence-based approaches are readily available to improve palliative care today. By implementing these guidelines and advocating for the integration of palliative care, healthcare professionals and administrators can significantly enhance the lives of patients and families facing serious illness.

Acknowledgments

Research Support from ACS Grant #PEP-10-174-01 (TS), R01CA116227-01 (TJS), 2R01CA106370-05A1 (TJS), and RC2CA148259 (BEH) from the National Cancer Institute.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest on this topic.

References

[1] Higginson IJ, Evans CJ, Grande GE. Palliative care: the Lancet Commission on palliative care and pain relief. Lancet. 2017;390(10086):2339-2350.

[2] Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska MK, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9911):1721-1730.

[3] Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: establishing essential components and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):4004-4011.

[4] Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

[5] American Society of Clinical Oncology. Provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880-887.

[6] Muir JC, Daly F, Elwyn G, et al. Implementing palliative care in outpatient oncology clinics: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29(3):352-359.

[7] Alesi ER, Martini C, Morino P, Piredda M, Carpenito J, Johnson J, Ausili E, Watson R, De Marinis MG. Effectiveness of early palliative care in advanced cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2023;37(1):22-34.

[8] Casarett DJ, Crowley R, Brassil K, et al. Satisfaction with end-of-life care in the Veterans Health Administration system: a retrospective survey of caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(3):194-203.

[9] National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 3rd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project; 2009.

[10] Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834-841.

[11] Fischer GS, Mazor KM, Baril J, et al. Implementation of advance directives in the outpatient oncology setting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(13):1743-1748.

[12] Earle CC, Weeks JC, Nattinger AB, et al. Chemotherapy use in the last month of life: is it cancer care or torture? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2641-2646.

[13] Center to Advance Palliative Care. Palliative care metrics. Available at: http://www.capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs/metrics/. Accessed 10 May 2024.

[14] Weissman DE, Meier DE. Measuring palliative care outcomes. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9(2):167-178.

[15] Billings JA, Pantilat SZ, Block SD, Wenger NS. Barriers to palliative care for hospitalized patients. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(1):59-66.

[16] Morrison RS, Meier DE. Palliative care consultation: how much difference does it make? J Palliat Med. 2002;5(5):753-762.

[17] Chan BK, Yip TF, Cheung YL, Fan DL, Lee SS, Chan PT, Lee PW, Ho CC, Tsang KW. Palliative care consultation service improves the quality of end-of-life care in a Chinese hospital. Palliat Med. 2007;21(1):15-20.

[18] Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Development and validation of screening criteria for referral to palliative care in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3239-3245.